Journalism is losing the culture war, because it's fighting last century's battles

When politicians can lie without consequence, our culture of fact-checking does little to stop them.

The Guardian’s SnowCuck-General* Martin Belam has hit the nail on the head with some of the problems inherent to the current fact-checking culture in response to a political movement prepared to flat-out lie to us:

[…] I’m reminded of Clay Shirky complaining during the US presidential campaign that, “We’ve brought fact-checkers to a culture war”, and Hussein Kesvani writing recently that “fact checkers are terrible at telling stories”, whereas the neo-Nazi “alt-right” movement is great at building and maintaining a narrative.

Here’s Shirky’s tweet:

Seeing my timeline during the convention last night made me despair. We've brought fact-checkers to a culture war. Time to get serious.

— Clay Shirky (@cshirky) July 22, 2016

Narrative. Culture war. These are important ideas to bear in mind, as you analyse this situation.

Narratives versus facts

Journalism in general is much more comfortable with facts and stories (in the 350 word, inverted pyramid sense) than narratives. The development of a narrative has been a fundamental part of the best digital native publishing, which tends to have a view and a tight focus, and then explore that narrative through posts and links. It’s a difference of form born of the contrast between the daily newspaper and the infinite scroll of the internet.

And right now, we’re seeing a full-on clash of those two cultures. And it’s not going well for the older version.

Belam again:

Infowars, Breitbart, Britain First – the sort of websites and organisations that are spreading the far right’s anti-Muslim, conspiracy-theory-ridden ideology – are not going to be afraid to double-down on spreading their message. Fact-checking their spurious claims is one thing – but what does it achieve? To really challenge the spread of this nonsense we need to work out what we are going to do about more effectively spreading the truth.

It’s a fine distinction, but picking away at the lies that build a political narrative does stop falsehood spreading – and that’s valuable – but it does very little to undermine the central narrative that the extreme right are putting out in the US. This problem is not exclusive to the US – we’ve certainly seen elements of the Brexit-supporting right in the UK do much the same. Given the current success in the States, I’m sure we’ll see more political movements copycatting this approach.

The guerrilla war on truth

However, Martin might be guilty of burying the lede a little – not down in the depths of the article, but in the comments (yes, those much-derided comments):

I started thinking that maybe we just have a rota and instead of us all having two journalists each fact-checking every Spicer appearance, we just have one news organisation with the short straw, and everyone links to their fact-check.

I mean, I can’t see it happening, but it’s interesting if you watched things like GamerGate organising, then they had a distributed crowd who could (mostly) agree on one line to take and then push out. It’s very efficient – and the media don’t really have that collaborative mindset because traditionally it’s been about exclusives and being first.

That latter paragraph highlights a really crucial issue. This battle over the narrative is an asymmetric one on a lot of levels. There’s no doubt that the weight of numbers – people – is still very much on the side of traditional media. Despite the brutal cuts to print newsrooms over the years, in aggregate we’re still talking a heck of a lot of people – especially when you figure broadcast into the equation. But those numbers are being wasted in repetition and duplication. This is the classic “over-supply of news” problem given a rather macabre twist.

Asymmetric information warfare

But it’s worth thinking about this in terms of asymmetric warfare. Look at the “opposing forces” Martin cites in the quote above:

Infowars, Breitbart, Britain First

These are all digital outfits and, in the case of Britain First, Facebook-first. These are people who have been honing their techniques for 15 years on blogs, forums and other online services. They were birthed in the rants against the “MSM” in right-wing blogs in the early 2000s, and they’ve only got more effective as the social media tools have got more powerful.

How many people today are aware of Breitbart’s origin’s as the late Andrew Breitbart‘s blog, where he developed a vision of publishing honed at The Drudge Report and The Huffington Post. Who remembers Milo Yiannopoulos as a would be mainstream right political and tech journalist in the UK? Or as a hanger-on to London and Berlin’s startup scenes?

Too many saw the #GamerGate battle as a side issue, relevant only to techies and geeks. But it was the testing ground for the techniques that the alt-right are using on a much wider scale right now.

This is a classic piece of asymmetric warfare, with a small, but highly-distributed but well-ordinated group of people punching far above their weight because they are focusing on a central narrative, and are using more powerful digital techniques than their sluggish, divided mainstream competitors. The newspapers and broadcast media have very big guns, but they’re all firing them at the same place – and it’s not where the opposition really are.

The Meme is the longbow of the 21st Century

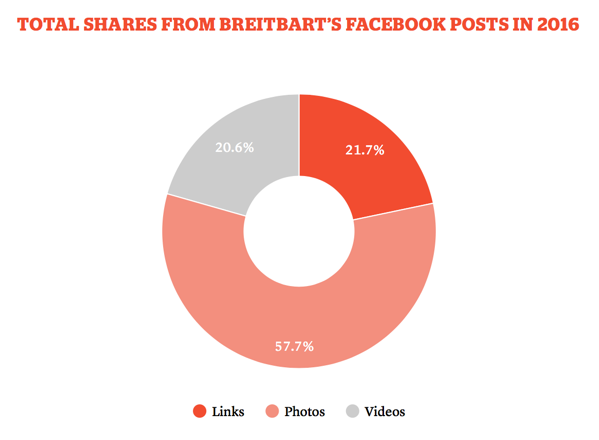

Don’t believe me? Look at this analysis of Breitbart’s use of Facebook:

[…] although Breitbart posted 12 times more links out of Facebook than images and videos combined, images and videos account for 79 percent of the total shares out of these top 100 posts. This disparity is even greater when you sum up the total shares of those 100 posts.

And this is the most shared post:

Geplaatst door Breitbart op Vrijdag 11 november 2016

Such a simple message. So central to the alt-right narrative. So easily spread. So easily assimilated into your thinking. This is the propaganda power of Facebook at its most might.

These are the digital tools of narrative warfare. Use of memes – and this is what this is – is a fundamental part of the new language of communication. But we’re still fighting with the tools of the last century – the 1000 word article, debunking the lies, but which reaches a tiny fraction of the people as that simple meme above.

Are we prepared to step up and use these tools? Or will be as the French at Agincourt, cut down by the new technology of the age? Then, it was longbows. In the culture wars, it’s memes.

Even when Spicer, Conway and the others use the traditional media, it’s to spread messages that will be picked up and repeated through digital – and especially social media – by their base. They are subverting the mainstream, and turning it into an additional and reinforcing distribution challenge even as they subvert trust in it.

Are you of digital or merely on digital?

At a fundamental level, there’s a war being waged between organisations which are on digital but are not of digital, and those whose very way of operating has been forged in the fires of digital culture wars over decades. And they’re using the power of direct communication – a power that was prophesied as long ago as 1999’s Cluetrain Manifesto, albeit in rather hippier form:

- Conversations among human beings sound human. They are conducted in a human voice.

- Whether delivering information, opinions, perspectives, dissenting arguments or humorous asides, the human voice is typically open, natural, uncontrived.

- People recognize each other as such from the sound of this voice.

Politics has fluffed around the edges of this. The Obama years used social media very effectively: remember this?

Four more years. pic.twitter.com/bAJE6Vom

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) November 7, 2012

Great image. But a carefully planned and staged image. Trump has subverted all that by talking like a person – although, admittedly, a particular kind of person – and his voice is undeniably his own. So many of his compatriots in this movement do the same. This has the power to make one of the elite – as Trump’s wealth and status make him – feel like one of the guys. They sound like people. We sound like – brace yourselves – elites hectoring people from our positions of power.

We won’t win the battle for truth with the weapons of the past. We need to take up the longbows of the digital era, and prove ourselves on the battleground of 21st century ideas.

*Sorry Martin, couldn’t resist.