Dominic Cummings’ blogpost, direct dialogue and its threat to mainstream political journalism

The Prime Minster's Chief Special Advisor outlined a new vision for the civil service in a blogpost — and with it, a new way of communicating policy, in way we need to pay attention to.

It’s interesting that, while US politics seems to be dominated by the President rapidly tweeting us towards World War III, the major event in British politics so far this year has been a blogpost.

Dominic Cummings essentially set out his manifesto for reforming the civil service and the way the British government operates in a blog post — and made clear his influences and thinking.

I’m not particularly interested in discussing the politics of this — and there’s not much point. Given the scale of the election victory that the Tories won last year, the “who” part of politics is no longer in question: it’s all about the “what” and the “how”. What’s really interesting is that one of the key figures involved in the current moment of British politics is doing his thinking on those questions in public.

For many readers of this blog, the thing that should give them pause is that this conversation was kicked off without the involvement of the mainstream press. Inevitably, some of the reaction has been sniffy. Here’s Stephen Bush writing in The New Statesman:

Part of getting viewpoint and cognitive diversity is advertising job roles in a wide variety of places. You are not going to get “viewpoint diversity”, still less the “weirdos” that Cummings says he wants in Downing Street, if your hiring process is confined solely to the readership of your personal blog and your existing office’s social and employment networks, even if it is then boosted by political Twitter.

This misunderstands what is actually at work here. Yes, Cummings is using his “personal blog” to make the job advert — but that’s giving him a control over the messaging that’s just not available through any other medium. He links extensively to his sources, and is direct about what working with him will be like — and the timescales involved. He is showing his working in public. He controls the narrative, and doesn’t have to depend on others to interpret and explain (or challenge) his ideas.

This is actually the sort of public discussion of ideas that many of us hoped blogging would bring to the public sphere a decade ago. And this, even if you disagree deeply with Cummings politically, is certainly a more healthy expression of that idea of government in public than Trump’s ever accelerating Twitter fury.

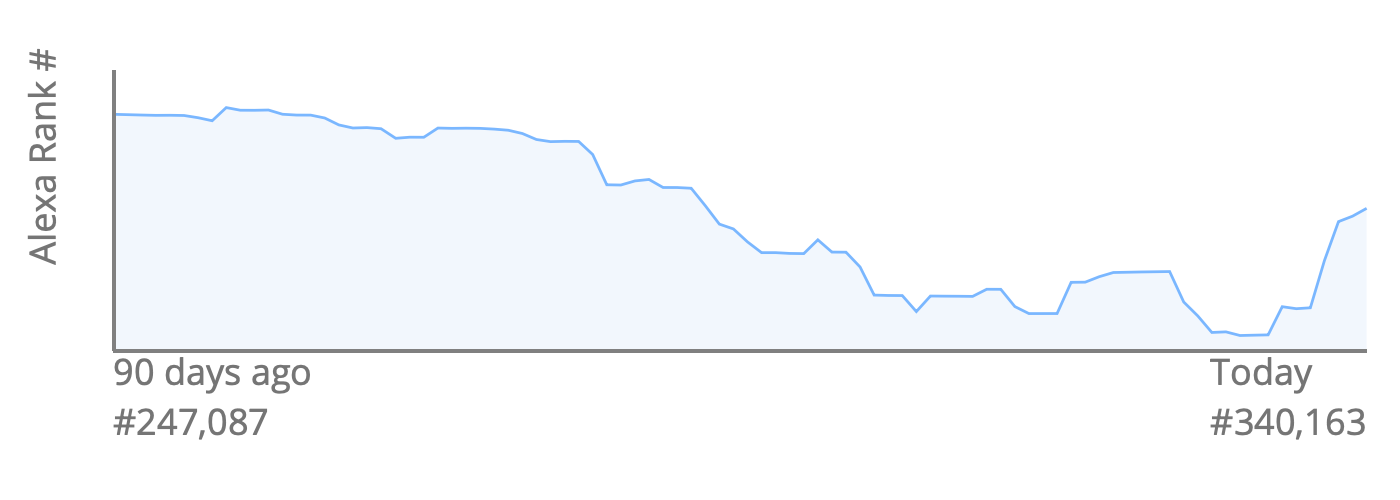

And he has to have known that the media and social media users alike would amplify that post. Alexa estimates show a surge of traffic to his site:

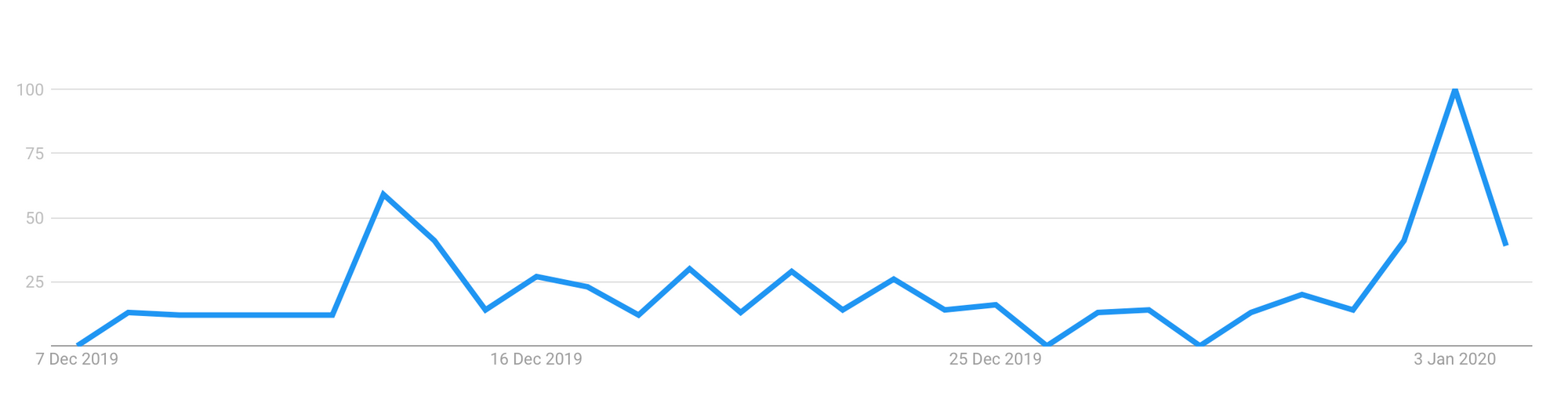

And Google Trends shows a matching spike in search interest:

It doesn't need to reach everybody - just the sort of people he's looking for. And many of them probably hang our in the blogging world of niche theories and deep expertise.

Mission accomplished. And without going the usual route of briefing the lobby.

Sidelining the lobby

Ah, the lobby. This has not been a great week for them. It’s worth paying attention to the fact that this post is, more-or-less, a policy announcement. And it was made without paying any attention to the lobby system. The first tase of the story actually came from a piece by one of the Conservative Manifesto authors, Rachel Wolf. It’s clear that Cummings has very little time for the traditional journalistic establishment. That’s threaded throughout his post, and it’s includes a direct swipe at the lobby:

In SW1 communication is generally treated as almost synonymous with ‘talking to the lobby’. This is partly why so much punditry is ‘narrative from noise’.

Cummings essentially bypassed that process by publishing his own thoughts and plans directly. This comes, of course, in the same week that a major change to the lobby system was announced — the consternation of many journalists. The system that has sustained and feed information to the UK’s political journalists is now clearly under attack on multiple fronts.

It’s certainly clear that Cummings does not respect most journalists. His general disdain for journalism (and marketing) is most clear here:

I noticed in the recent campaign that the world of digital advertising has changed very fast since I was last involved in 2016. This is partly why so many journalists wrongly looked at things like Corbyn’s Facebook stats and thought Labour was doing better than us — the ecosystem evolves rapidly while political journalists are still behind the 2016 tech, hence why so many fell for Carole’s conspiracy theories. The digital people involved in the last campaign really knew what they are doing, which is incredibly rare in this world of charlatans and clients who don’t know what they should be buying.

Let’s ignore his sideswipe at Carole Cadwalladr for now — it’s interesting in its own right, and I’ll come back to it later on.

Pretty much everything else he says in that paragraph is correct. Digital advertising and marketing is changing at a rapid clip, and yes, three years ago is an eternity in this space. Yes, very few journalists really understand the dynamics of marketing and communications via social media. This is partially due to the distorting effect of their obsession with the public skirmish field that is Twitter, but also down to not being aware of how much happens in places where we can’t see that activity. The public-facing numbers may not have much bearing on what’s happening in places we can’t see into.

The phrase “charlatans and clients who don’t know what they should be buying” will resonate with anyone who has worked in this space. The prevalence of vanity metrics, and the absence of a deep understanding of both purpose and effectiveness in social media use is an unquestionable fact.

Here’s the key point: we cannot effectively hold a Cummings-steered government to account unless our political reporters become much more sophisticated in their understanding of digital campaigning.

The dangerous seduction of Twitter

Which brings us back to his swipe at Carole Cadwalladr, who has done more reporting around the use of digital media in UK elections than most journalists — and is certainly the public face of the journalistic enquiry into the nature of the Vote Leave victory back in 2016. Many on the Leave side have dismissed the allegations as “conspiracy thinking”, as Cummings did here.

Cadwalladr replied — but on Twitter:

Hugely flattered to be cited in the weirdest job ad in the world. This is to remind all UK journalists that when Dominic Cummings talks about ‘Carole’s conspiracy theories’ he’s talking about the biggest breach of UK electoral law in 100 years, a matter now in hands of Met police pic.twitter.com/CdpqNwT5id

— Carole Cadwalladr (@carolecadwalla) January 2, 2020

Which is lovely and all, but it means that her response is way harder to find than the original piece. It’s great for the Twitter bubble, but not for everyone else. That’s why hacks like Threadreader exist - to effectively turn a bunch of Tweets into… a blog post. And then The Drum encapsulated the response in an actual article.

Cummings’ post is there, in its entirely, in a form he controls — all 3000 words of it. Cadwalladr’s repsonse is lost in the flow of Twitter, and has to be extracted from a closed platform in various ways. This is an asymmetric control of the message.

(Incidentally, Cummings deleted his Twitter account back in 2017 — and it is unclear if the recreated account which came online later that month is actually him. )

As Cummings concludes his post:

I will post some random things over the next few weeks and see what bounces back — it is all upside, there’s no downside if you don’t mind a bit of noise and it’s a fast cheap way to find good ideas…

If he is — quite genuinely — listening, then feedback is beginning to emerge. It’s not in the nitpicking and point-scoring of Twitter, though. It’s in long and thoughtful posts. For example, Matt Jukes, who used to work in digital at the Office of National Statistics, wrote his own version of the job ad:

While Mr Cummings is busy fetishing scientists and economists I’d be poaching lawyers. Not just any lawyers but those rare birds that understand the internet-era. Whether they come from the Open Rights Group or EFF networks, or Linklaters or the bloody Facebook policy team I’d want to hire real, deep expertise in privacy, data sharing, copyright and basically the world we live in today. Experts who understand the nuances of things like GDPR and the Data Protection Act. Who are able to articulate things clearly and broadly (backed by the Cardinal) and who are able to turn the dial a bit on the risk appetite of so many in the Civil Service. FUD has crippled so many opportunities because the advice is so often lowest common denominator stuff.

Government Digital Service co-founder Mark O’Neill wrote a post in response, giveing almost point-by-point responses drawing on his own experience of working with the Civil Service:

As for the “Super-talented weirdos”, the Senior Civil Service is a monoculture and reacts very badly to those outside that culture. I have seen and indeed experienced the extreme bullying and harassment of those who do not fit into the classical mode. Creating a more diverse culture will require very supportive and empathetic leadership and management.

It will also, I would suggest, require a degree of single-mindedness and even ruthlessness to stop the “immune system” of the Civil Service kicking out the new. It also suggests that this would have to be a long-term project — more than the Skunkworks that some suggest — because otherwise, the organisation will return to business as usual as soon as the external pressure is gone. That’s pretty much what happened to GDS, in the end.

Oh, hang on — what just happened there? We started to have a dialogue of experience and ideas.

That’s rather more experience that Twitter users quipping out 280 characters of snide response, isn’t it?

If Cummings continues down this path, we’re in for a torrid time as an industry. Policy and implementation discussions are going to happen in detail, in public, without going through us. It’s worth noting that Rachel Wolf, whose Telegraph piece first signalled the Civil Service changes, wrote a deeper piece about the intentions of the manifesto a few weeks before. These discussions are already happening.

And as for the voters, well, they are going to be communicated to directly, via social media, without going through us.

When we are no longer the gatekeepers of political information, what are we? What value do we bring to the process? This is a question the US press have been asking for over three years. Now we’re facing something similar. That we’d end up here has been obvious for at least 15 years.

We’re out of time to find the answers.

Image by Marco Verch and used under a Creative Commons licence