20 years ago

Two decades ago, a series of terrorist attacks shook London. And I found myself on the cusp of two worlds of journalism.

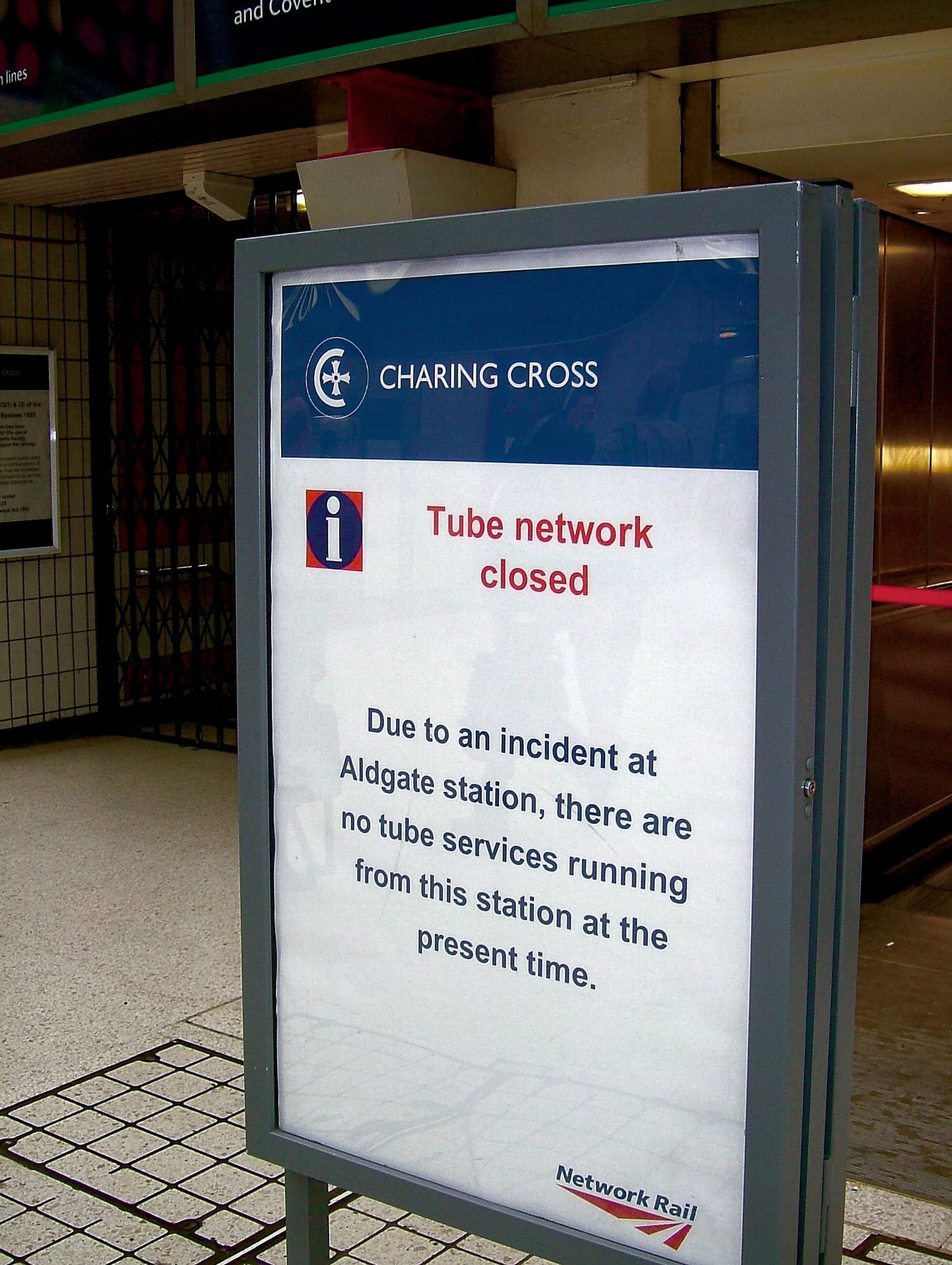

It was only when I arrived in Charing Cross that I realised something was wrong. The station was near-deserted, and all trains out had been cancelled. Something was going on – but what?

This was 2005. I had a mobile phone, but it was an old Nokia, and I certainly couldn’t look up the news on it. No iPad and no mobile broadband. I had a laptop in my bag, but I’d have to hunt down Wi-Fi.

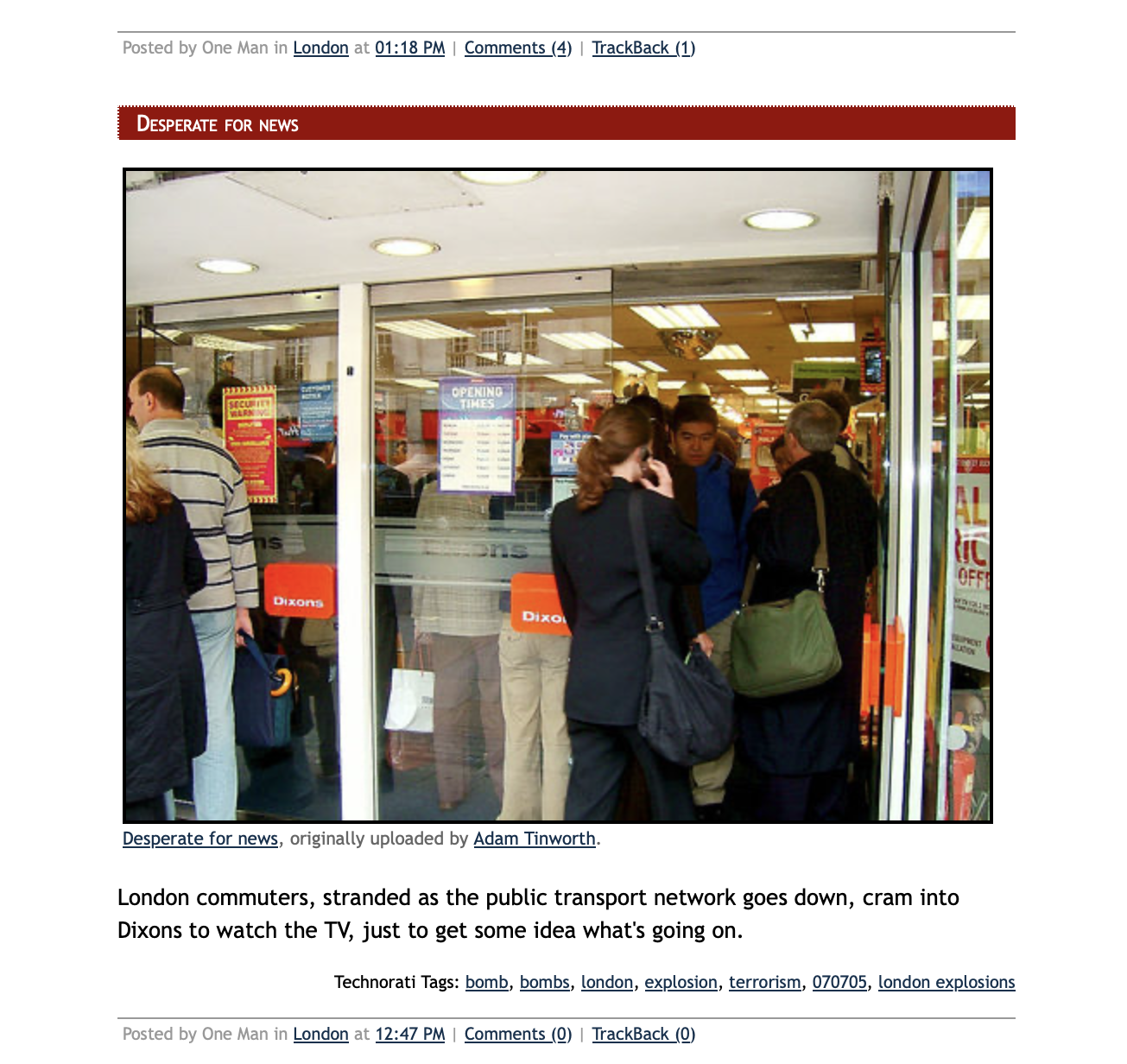

As I wandered down the Strand, the atmosphere was weird. There were more people on the street than normal, and the tubes were shut. Eventually, I peered into the window of a Dixons, trying to see the news stories on the TV. I tried to get inside — but I couldn’t. It was packed.

I gave up, walked further along the Strand to a coffee shop, and opened my laptop. Over the sluggish Wi-Fi, the story emerged. Bombs on the underground. Bombs on buses. The details were scarce yet. But there was only one thought on my mind: Lorna. She’d been on the tube to St George’s where she was a postdoc. Was she OK?

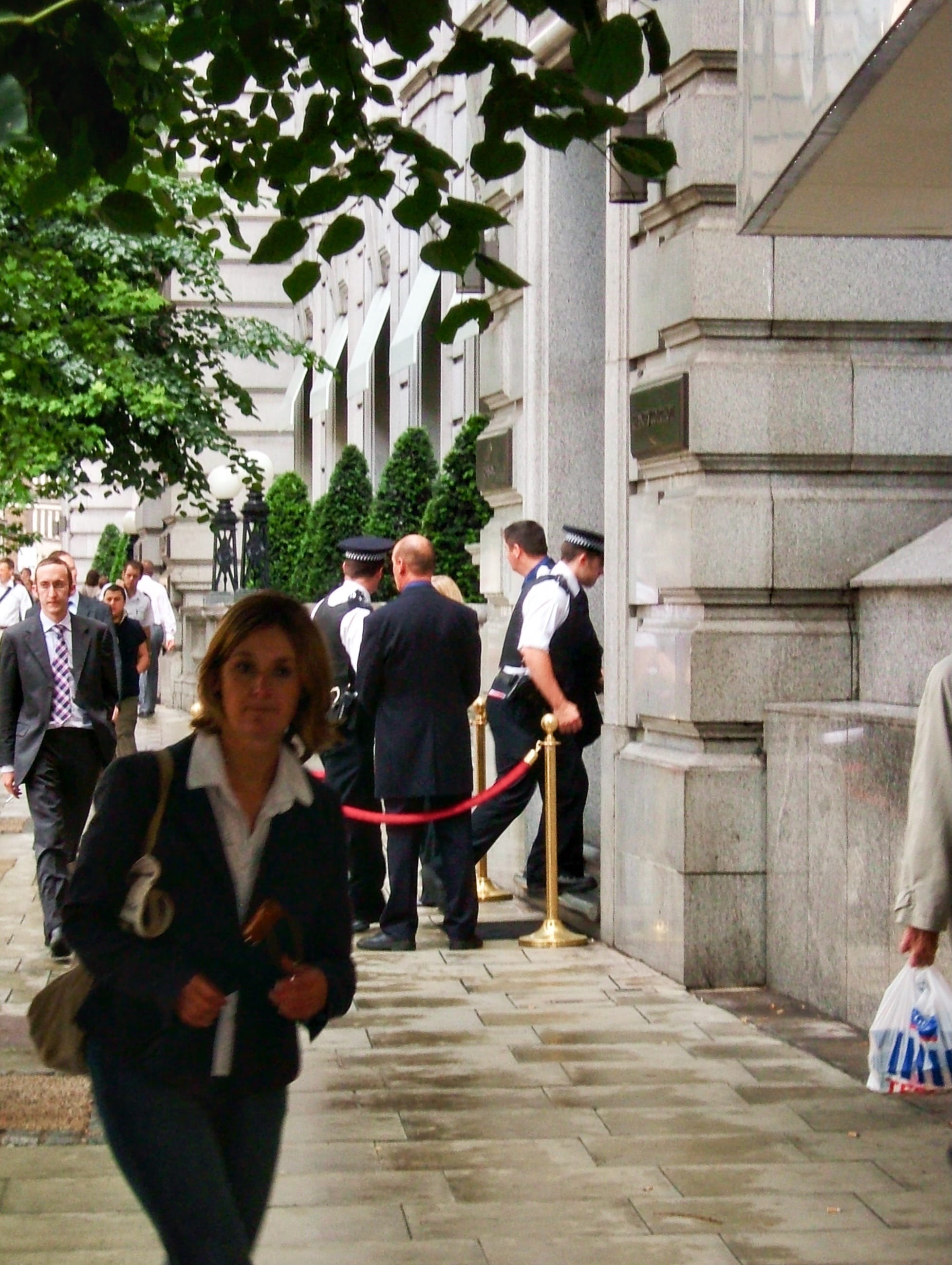

I tried calling her work phone, but couldn’t get through. (I later learned that the hospital had gone into emergency mode, shutting non-essential things down and preparing to receive mass causalities. My wife was fine, just incommunicado.) With nothing else to do, I headed to the office. But as I approached the Holborn base of Estates Gazette, it was clear that London was still in the throes of dealing with the crisis. There were police cars everywhere.

By the time I got to my desk, the wider picture was emerging. News travelled more slowly in those pre-smartphone days, and we didn’t yet have social media or smartphones to provide today’s volume of eyewitness media. I still hadn’t heard from Lorna, and couldn’t concentrate. So, I went out again with my camera (yes, a compact digital camera. My Nokia wasn't up to the job), as I knew that a bus explosion had happened just around the corner.

I couldn’t get anywhere near, of course, as the police had the whole area sealed off:

But what I could catch with my camera were the professional photographers on the same hunt I was:

And the police, commandeering a hotel opposite the office as a base of operations.

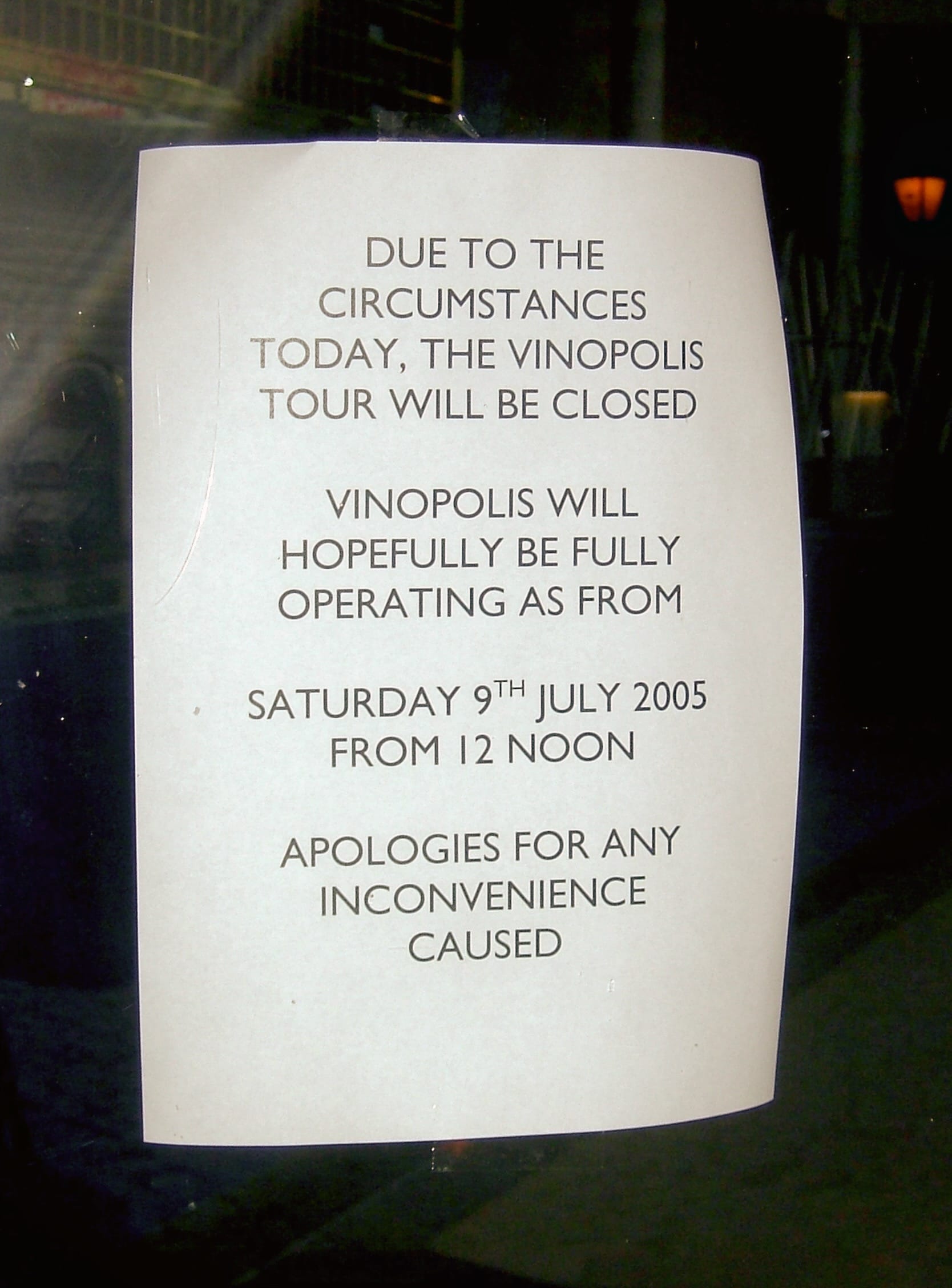

Eventually, I returned to my desk. We had a weekly issue to fill, whatever was happening. I eventually got hold of my wife, learned she was safe, and the need for displacement activity evaporated. But the journey home was to prove difficult. The tubes were shut. The buses were packed. And most of the central London terminuses were shut.

I headed home via London Bridge, hoping that the station would be open and running trains. And it was. However, that was a strange, strange journey, through an unsettled, but determined London.

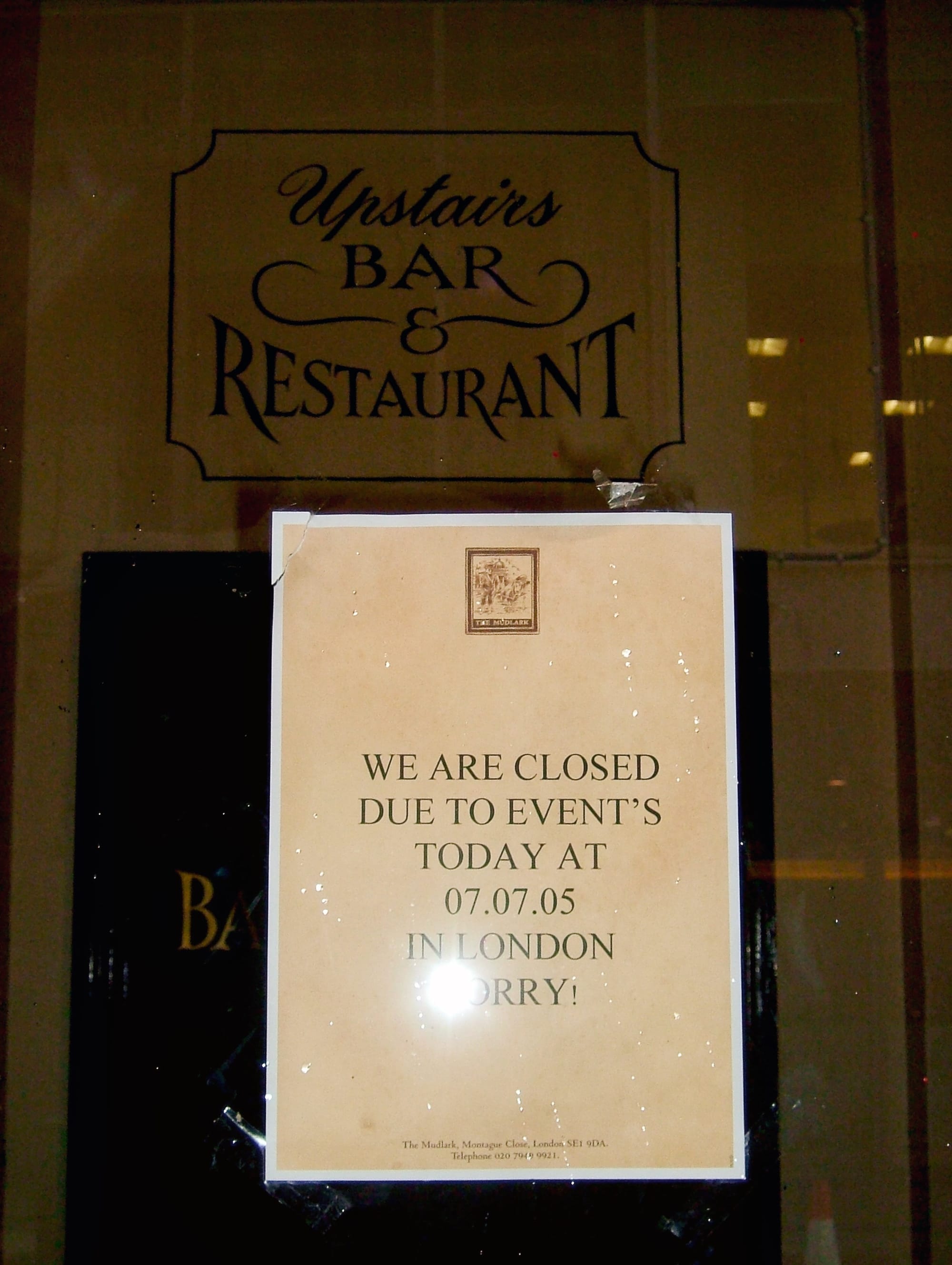

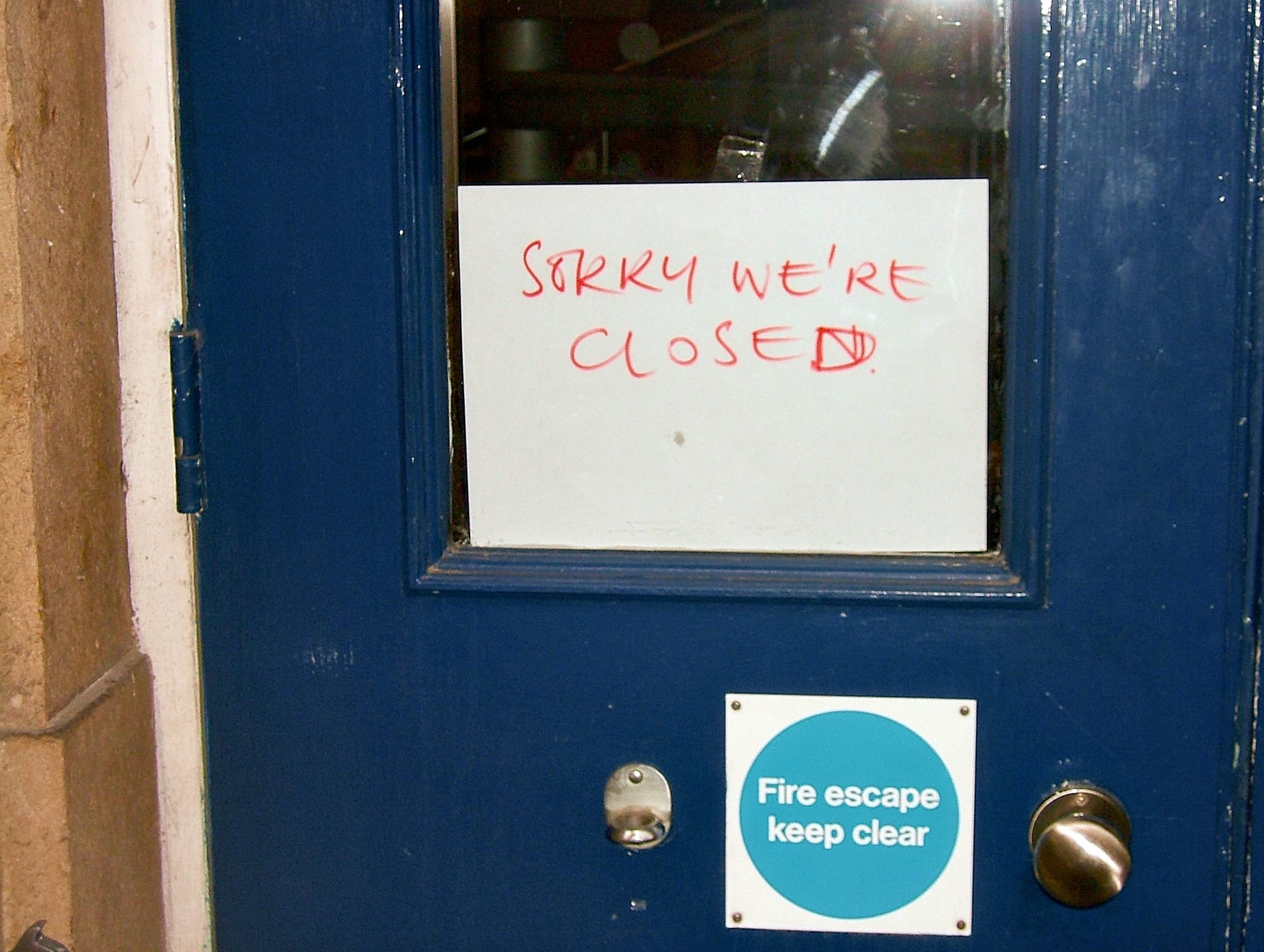

A London that was both closed, but trying to keep going:

It wasn’t my first terrorist attack. Years before, when in the student halls room of my then-girlfriend, I’d felt the Bishopsgate bomb go off. But this was on a different scale, and it marked the cusp of a profound change in the way news spreads. My photos, uploaded to this very blog, were among the first “eyewitness media” in the pre-social media age.

I ended up appearing in academic papers and one book, looking at the phenomenon. (Much to my chagrin, they skirted around the fact I was a professional journalist, albeit a business one, as it muddied the waters of the citizen journalism narrative they were exploring).

If, God forbid, an attack like this were to happen today, we’d all know in minutes. The news would rip around the city, the country, the world, in a matter of minutes. Social media and messaging apps would see to that. We all have a broadcast quality camera in our pockets these days. We would no longer spend those long, long minutes in ignorance, trying to understand what was happening. But, perhaps, the fear would be magnified, and the reaction stronger, just because of the speed of the news and the immediacy of the imagery.

7/7 was a tragedy that rocked the City. But it was also a liminal moment, right on the cusp of the slow news and smartphone eras, when how we learn about and react to tragedy would change forever. It was an experience that changed me, and changed the vector of my life.

Those events of two decades ago somehow feel like both only a few years back, but also something from a different life. And, perhaps, both feelings are true.