Journalism’s return to community is necessary – but risky

“Community” and ”Audience” are not synonyms. If you want to turn the latter into the former, there are some key skills you need.

This morning, I was on a mentoring call with a client for a new newsletter project they’re launching. (The trial goes live next week, and to say I’m excited would be an understatement. But then, I don’t do consulting unless I believe in the product…) One of the things we ended up discussing was the community element that’s inherent in newsletters, but which all but the best practitioners tend to forget. It’s easy to see newsletters as a marketing tool, a way of getting readers back to our “main” thing, whatever that thing tends to be.

But as long as you have a human voice opening the newsletter, and a reply email address on the newsletter that actually works, newsletters can be a great tool for community building. They can develop their own in-jokes, shared concepts and interests – and the potential of the recipient to also become a contributor, cementing the relationship. We specifically talked about how readers can become source software leads, and experiences I've had around that. Communities around journalism can be valuable in all sorts of non-obvious ways.

But communities need nurturing to development. They are built on relationships, and you require expertise to manage them. Community management is a skill, one that requires training and experience. Even the big platforms have realised this, and end up hiring Trust and Safety teams. (If you want insight into all that entails, well, you should be subscribed to Ben Whitelaw’s Everything in Moderation because there is truly no better source.) But I’ve found myself thinking extensively about smaller scale community management again because, 20 years on, the journalism world is finally realising its power.

Here are some notes you might find useful.

The one thing you need to understand about community

As journalism re-embraces community as a core component of audience work, we’re going to see publishers make the cardinal sin of community management:

Believing they own the community.

You can never own the community. You can host it, sure. You can — and should — serve it.

But you never own it.

I experienced this first hand back in the 2000s, when we were actively building community around the B2B brands I was working with. A decision by the company’s IT department to enforce a platform move on a highly successful community cost us the relationship with that community. And that created a competitor for advertising and attention, and they relocated to their own platform, and sought sponsorship to cover the costs.

(First published in part on LinkedIn)

Communities aren’t fungible

The experience I described above was the best part of 20 years ago. This was published this week:

When a platform migrates its user base to a new architecture, the implicit promise is that the community will survive the move. When a city demolishes a public housing block and offers residents vouchers for market-rate apartments across town, the implicit promise is that they'll rebuild what they had.

These promises are always broken, and the people making them either don't understand why, or they're relying on the rest of us being too blind to see it.

That’s JA Westenberg. And there’s plenty of useful community hosting insight in the post:

The internet has run this experiment dozens of times now, and the results are consistent. When a platform dies or degrades, its community does not simply migrate to the next platform, it fragments, and the ones who do arrive at the new place find that the social dynamics are different, the norms have shifted, and a substantial number of the people who made the old place feel like home are gone. LiveJournal's Russian acquisition scattered its English-speaking community across Dreamwidth and eventually Twitter. Each successor captured a fraction of the original user base and none of them captured the culture. The community that existed on LiveJournal in 2006 is extinct and cannot be reassembled. The specific conditions that created it, a particular moment in internet history when blogging was new and social media hadn't yet been colonised by algorithmic feeds and engagement optimisation, no longer exist.

This is something to bear in mind, as community becomes a buzzword in the journalism and audience space again. There is a deep, 30 year plus, experience of what makes online community work, and much of it lies outside journalism. If we’re going to host communities again within the world of journalism, we need to start tapping into that history.

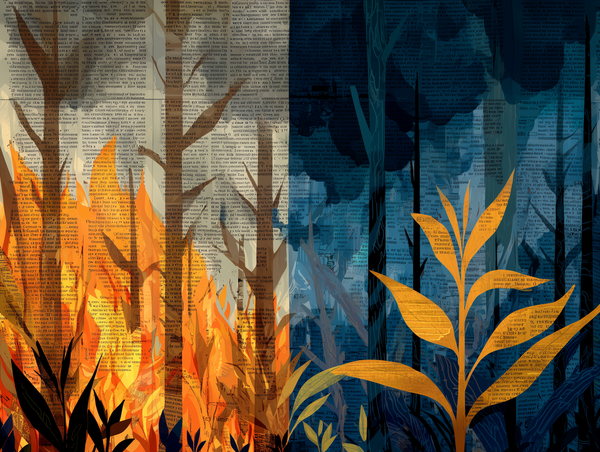

And that history shows us that community is challenging to build – but easy to destroy. It’s easy to mouth the platitudes about relationships and support, but much harder to put the time and work into managing and providing what the community needs. And one bad mistake can destroy that community. Once you see the community as your community, you lose the host mindset, and adopt the owner one. And that's a dangerous route.

If you want a recent journalism-specific example, remember that one action that the Washington Post readership considered a betrayal cost the title 10% of its paying subscribers.

Back to Westenberg:

Communities are not resources to be optimised and they're not user bases to be migrated. They're the accumulated residue of people choosing, over and over again, to remain in a relationship with each other under specific conditions that will never, ever recur in exactly the same way.

And the keyword there is relationship. Hosting a community is entering into a relationship. And with that comes commitment and effort to maintain it. We have the financial incentive now: community members have a great propensity to becoming paying members. We just need to be ready to commit to the work.

And community management is a skill, an area of expertise in its own right.