Report and Connect: a manifesto for the survival of journalism in the AI age

A call for us to stop letting the tech companies define our work, and reset our focus on the audiences we need to survive

What happens when a new technology starts changing all your old assumptions?

We should be used to that question by now. We’re on our fourth or fifth go-round on it in my lifetime. This time, it’s AI, but it’s been computers, and the internet, and smartphones, and social media in previous waves.

Here’s the lesson we need to cling to: technology changes, people don’t. David Mattin even named his newsletter after the idea: New World, Same Humans, because it’s the lens through which he views everything.

So, as AI starts munching on the work we used to do, as it threatens our businesses and our audience approaches, what do we do?

We turn to our base humanity, and we look at how we can serve fundamental human needs, that AI simply cannot do with anywhere near the same effectiveness.

We don’t need news

Let’s be clear about this, painful though it might be: news is not a fundamental human need. Is it useful? Yes. Does societies function better with good, unbiased reporting? Unquestionably yes. But it’s not a need. It’s a “nice to have”. Or, possibly, a “very nice to have”.

So, what is the human need that underpins news, and journalism more generally? It’s something we’ve lost sight of, as we focus on the product – journalism – itself, without understanding the context within which that product operates. The need for news is underpinned by the need for connection, or perhaps, community. Without community, humans do not thrive. With it, we become more than we are individually.

We are fundamentally social creatures. Loneliness is associated with both mental and physical health problems. Arguably, it’s comparable with cigarette use and alcohol abuse as a threat to your health. From its very earliest days the internet has been used as an expression of that profound need for human connection, from email discussion lists, to newsgroups, from forums to blog, and through into social media.

News as social object

News — communication about and for the social group — is an expression of the need for community. If you look back to the pre-digital forms of publishing, they were all, to a greater or lesser extent, community focused:

- Trade press: professional communities

- Local press: geographic communities

- Consumer press: passion communities

- National press: political communities

We, as journalists, facilitate human social thriving through enabling information exchange.

But communities require something to gather around. We often call this the “social object” that is at the centre of that community. If you look back at the history of journalism, as we just did, titles that thrived tended to serve communities that gathered around particular kinds of social objects.

But the modern era offers us something more: the potential for journalism itself to become a social object. The oft-discussed “flight to niche” is just an expression of our sorting ability to serve more targeted communities through the internet’s nack of allowing us to find others like ourselves. We’re no longer dependent on there being enough people in a particular community for it to be worthwhile for WH Smith (or should I say TG Jones, these days?) to stock a magazine for that group.

If like-minded people can find you through a search or social media, there’s the potential to build a content business serving them. And then to deepen that relationship by not just serving them content, but facilitating connection between the people in that community.

The content conundrum

The challenge, of course, is that AI is starting to eat away at the content businesses. AI can produce “content” far faster and cheaper than humans can. The internet unleashed a total wave of human-created content, and that’s become a tsunami with the advent of AI-generated slop. Content is not the differentiator we think it is.

The original sin of the 2010s was letting tech companies take community away from us. We provided the content, the formal media platforms provided the community tools. Turns out that the community tools were more valuable, and people stayed there, even as Facebook pushed more and more of our content out. (And, ironically, allowed disinformation to have a level playing field with us.)

But we only truly have an audience when that audience feels they are in community with us, and we are with them. Emergent media understands this much more deeply than we do. They’re all “hey, guys” on YouTube, and talking directly to the camera on TikTok, while we stand above it all, with our neutral tone of voice and slight disdain for our readers. One of the sources of our deep and growing trust problem with audiences is this: in an era where so much of the media they consume prioritises connection, community and personality, we so often go the other direction.

Reconnecting with our audiences

And this is what we need to reverse. We can’t afford to have “local” news journalists that have never been seen at local events in their patch because they’re slaving away at an impossible story count target in some regional “content hub”. We can’t afford to keep mocking and mismanaging the comment section. Why? Because those maligned commenters are some of the people who care enough about what we’re doing that they will take the time to interact on our platform, rather than the innumerable social media ones.

Not only that, but we need to accept that we don’t have a right to exist, we have to keep proving our value again and again and again to each new generation, even as media shifts around us. And we can only do that by connecting to the communities we serve.

And, as AI devalues content generally, we can shore up the value of our journalism, by building connections between the people who produce it and the people who consume it.

Serving your communities

Every journalist serves at a minimum two communities:

- The people they report on

- The people they report for

In some cases, these are largely identical. For example, in the trade press, the people you are reporting on are largely the people you are reporting for. It tends to keep those journalists remarkable honest and ethical because that overlap makes it really difficult to get away with bad behaviour and still have a business…

On the other hand, they can be quite distinct. The national news sites tend to report on politicians, business people and celebrities for a generalist audience. Too often, journalists prioritise their connections with their sources – the people they’re reporting on – over their connections with their audiences, the people they serve.

We need to reset this orientation.

Content + Connection = Viable Business

In an age where people can extract information (albeit of dubious accuracy) from AI chatbots, you need to give them more than just information to have a sustainable business. You can do that by giving them context, analysis, and even opinion. But for that to be effective, you also have to win their trust – something we’re struggling with right now. And to rebuild trust, we must rebuild connection.

The social platforms ate our lunch in the 2010s because they offered connection, and then let us pipe our content into the connections they’d let users build. Building a toolset for connection turned out to be more powerful than providing the information that fuels that connection because it speaks to the more profound need in humanity, rather than an expression of that need.

What we now call “audience work” is really just a refocusing of journalism around what it always was: a service performed for a community. I sometime use this phrase in my training and lecturing work:

Journalism is not an abstract art, it is a service provided for communities of interest, to improve their lives.

We need to fully assimilate that fact, and stop worshipping news as an abstract value. It’s time to learn to ignore the seductive whispers of its high priests, the exclusive, the angle, and the clickbait. And we need to spend less time looking at our competitors for validation, and more time looking at our audience and what they want and need.

If we do this, many of the challenges we face look less intimidating.

Flighting the future with connection

We survive “Google Zero” by proving to our audiences that they don’t need Google. Think it can’t be done? I’ve worked with one medical title where a considerable chunk of their traffic comes direct to their clinical search page. They’ve built connection and trust with their readers over years and decades such that they will go there first for the information they require. And I don’t see AI rushing to get in the way of that. “I asked ChatGPT, and it told me to use this drug” will not be a useful defence in a clinical malpractice hearing…

We can start to depower dis- and misinformation by drawing our core audiences away from social platforms, and into community spaces under our control, where they can find both connection and the journalism that enriches that connection. In fact, this seems like a moral obligation at this point, given how fluid a vector the mainstream tech companies’ platforms are for toxic content.

And we make the human, fact-check, researched nature of our journalism a feature. No, more than that, a selling point. Through trust between our journalists and our audience, we become islands of quality connection and information in a sea of cheap content, shallow relationships and toxic misinformation.

Reskilling the newsroom

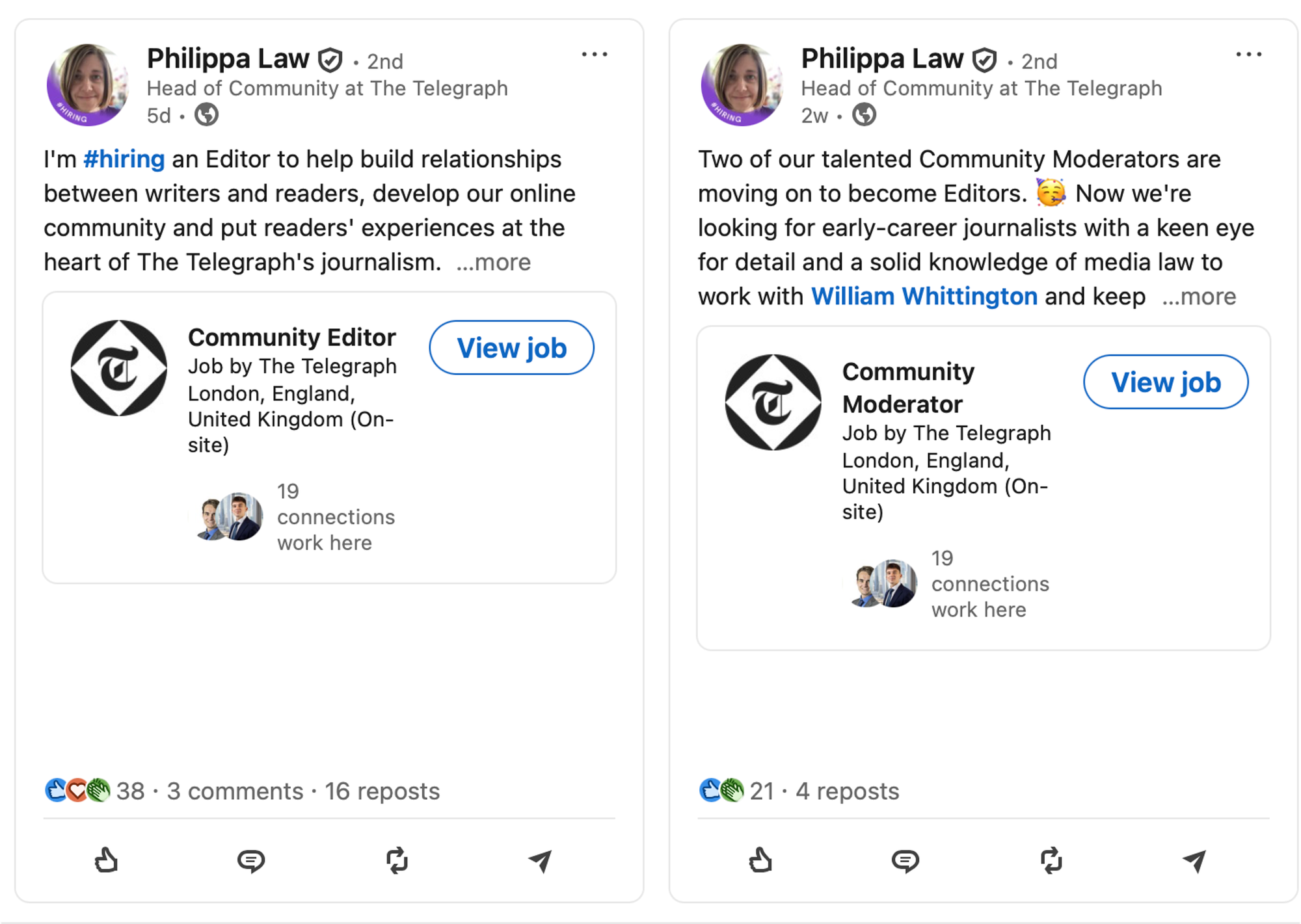

This is a tough job. It requires bringing new skills into the newsroom, ones we abandoned over 15 years ago. But, if you look around, you can see newsrooms doing this already. I had this screenshot in my slides for welcome week at City St George’s:

Why? To open their eyes to the fact that there are other ways of doing journalism, and making that journalism matter, than the traditional ways.

I’m increasingly thinking of the 2010s as the decade of delusion for our industry. After starting to adapt to the challenges of the internet in the 2000s, we retreated to our comport zone in the following decade. We ended up growing lazy about our relationships with audiences, as the social platforms and the search engines fed us a steady flow of soporific traffic. But they’ve choked that off, and are in the process of strangling what’s left.

We’re halfway through the 2020s now, but there’s still time to make it the decade of reawakening and reinvention. We need to stop letting the winds of tech blow us off course, and set ourselves a firm course, towards connected journalism, with audiences that trust us, and who see us as part of their community.

If we can get there, we can build a stage for a new renaissance of journalism in the 2030s.