Journalism needs its own post-COVID inquiry

Sure, we didn't make decisions that killed people. But could we have helped people navigate the pandemic better than we did?

Yesterday's session with former UK government advisor Dominic Cummings before a seven-hour joint session of the Commons Heath, and Science and Technology committees dominated my Twitter feed, many of my podcasts and, if I was to be honest, a significant chunk of my own attention.

Lurking in the background, but easily forgotten in the rush to cover and discuss the big UK politics story of the day, was that they were looking into how government made decisions that had consequences for the lives of everyone in the country. And, more to the point, that they were failing to make decisions in a way that quite possibly cost thousands of lives.

It wasn't just today's story. It was something that was unpicking a period of time that had profound consequences for many.

Those of us who got Covid bad aren’t watching this stuff with Cummings as if it’s a Westminster soap opera. This is why we nearly died and thousands more did.

— Michael Rosen 💙💙🎓🎓 (@MichaelRosenYes) May 26, 2021

How much of the reporting reflected that? Some sites rose to the challenge. For example, Kate Proctor contextualised it well for PoliticsHome, as did Robert Booth for The Guardian.

But pieces like these are still the exception, not the rule. Good journalism often requires walking a fine line between detaching yourself from the story enough to write it objectively, while also keeping in mind that we're talking about people with real lives and relationships. Often, those poor decisions we make when we stray onto the wrong side of the line stick in people's minds for years afterwards, eroding trust in what we do.

Earlier in the week, I had an optician appointment. She asked me what I did — and when I talked about my work, she rapidly brought the subject around to Milly Dowler and the alleged hacking of her phone. That's a story about a (still unproven) offensively bad journalistic decision that's nearly two decades old, and yet resonates with people today. Yes, The Guardian corrected that story, but nobody remembers that part (myself included, in fact — thanks to Charlotte for reminding me).

The pursuit of the story does not justify everything in the minds of our audiences. And they do not forget when we make big mistakes.

The story isn't everything

Charlotte Henry wrote about the disconnection that can happen when journalists have their eye on the story, but not the people it can impact, in a recent edition of her newsletter:

While many journalists have worked exhausting hours in difficult circumstances to keep people informed about the COVID-19 pandemic, the glee with which too many others have relayed this ongoing dystopian nightmare is stomach-churning and disrespectful to readers and viewers. The journalists may be getting a thrill from covering 'the biggest story of their lifetime,' but those consuming it are often worried about their finances, their health, their future, their families... or just plain bored.

This is, and was, counter-productive. Within months of the start of the pandemic, the Reuters Institute found evidence of a surge in news avoidance. It's not just the conspiracy theorist that believe we had a role in stoking fear. Many more people in the reality-based community will remember the time that bad news was coming at them relentlessly and inescabaly, when they badly needed distraction just to cope.

We, for a while, failed them.

Who is news for?

Nearly a decade ago, Joanna Geary (now a big-shot at Twitter) linked to a quote by Rupert Murdoch of all people, that resonated with her then, and still resonates with me now:

“I can’t tell you how many papers I have visited where they have a wall of journalism prizes — and a rapidly declining circulation. This tells me the editors are producing news for themselves — instead of news that is relevant to their customers. A news organization’s most important asset is the trust it has with its readers — a bond that reflects the readers’ confidence that editors are looking out for their needs and interests.”

(The full submission is archived here.)

I've been banging on about the dangers of serving a “platonic ideal of news” for, oh God, over a decade. But this is a very real example of how dangerous it can be. Getting seduced into the adrenaline rush of the biggest story of many of our lifetimes is easy. Remembering that we serve readers — real, living, human beings with emotional needs as well as informational ones — is hard.

But if we're serious about the shift to reader revenue and membership models, we need to get much better at doing so. Those relationships are based on trust, and a sense that the jorunalists have the readers' best interests at heart. While the desperate need for information duringa. pandemic did lead to a subs boom in some quarters, maintaining those subscribers will require a very different set of journalism, as we edge towards the end of the pandemic.

The self-inquiry into journalism in the pandemic

I wonder if the industry is capable of doing what the UK system of government is trying to do right now: put itself through a period of self-examination about what it did and how it served the public during the pandemic. Some parts of the media will come out of it well. The much-maligned “trades” — the B2B sector — often rose to the challenge, getting the information their readers needed, or, in the case of the medical titles catering to doctors, nurses and health service professional, often leading the reporting on what was happening.

Many consumer titles responded by forming communities, to help readers (and the mags themselves) survive the lockdown by focusing on the things they loved.

But, I would argue, too many of the mainstream news titles were too slow to realise that many people couldn't cope with relentless bad news about hospitalisations and deaths being pushed at them in push notifications and newsletters, with no easy escape hatch.

Many got there in the end, with the rise of “good news” newsletters, and more prominence for the COVID-free sections of the site. But let's see if we can take the time, once the pandemic passes, to figure out what we did wrong, and make sure we don't make the same mistakes again.

Digital Journalism and Online Culture

Talking of Cummings and his evidence, the tagline of this blog has long been “digital journalism and online culture”. If you ever wanted evidence of how entwined the two are, I present this for your edification:

Quick Links

- ❤️ Facebook now offering the ability to hide like counts on both Facebook and Instagram. The “social proof” aspect of this feature has been instrumental to the growth of the platforms — but may be one of the single most damaging aspects of them. This does feel like too little, too late — and smacks a little of pulling up the ladder after themselves.

- 🎤 Casey Newton talks to Instagram, who (unsurprisingly) disagree with my take.

- 🕵🏻♂️ Influencers are being approached to spread misinformation about vaccines. Easy to do, big reach, flies under a lot of people's radar. Chilling.

- 👻 Lovely to see Isabelle move Borderline from Substack to Ghost, and create a great new version of her site in the process.

Tweet of the Day

Another thought on Facebook @OversightBoard: they made the same recommendations many have for years while receiving a 6-figure salary & are applauded. Scholars+activists undoubtedly helped educate & influence them. Many took risks to speak out, without making big $. Don’t @ me.

— Yael Eisenstat (@YaelEisenstat) May 8, 2021

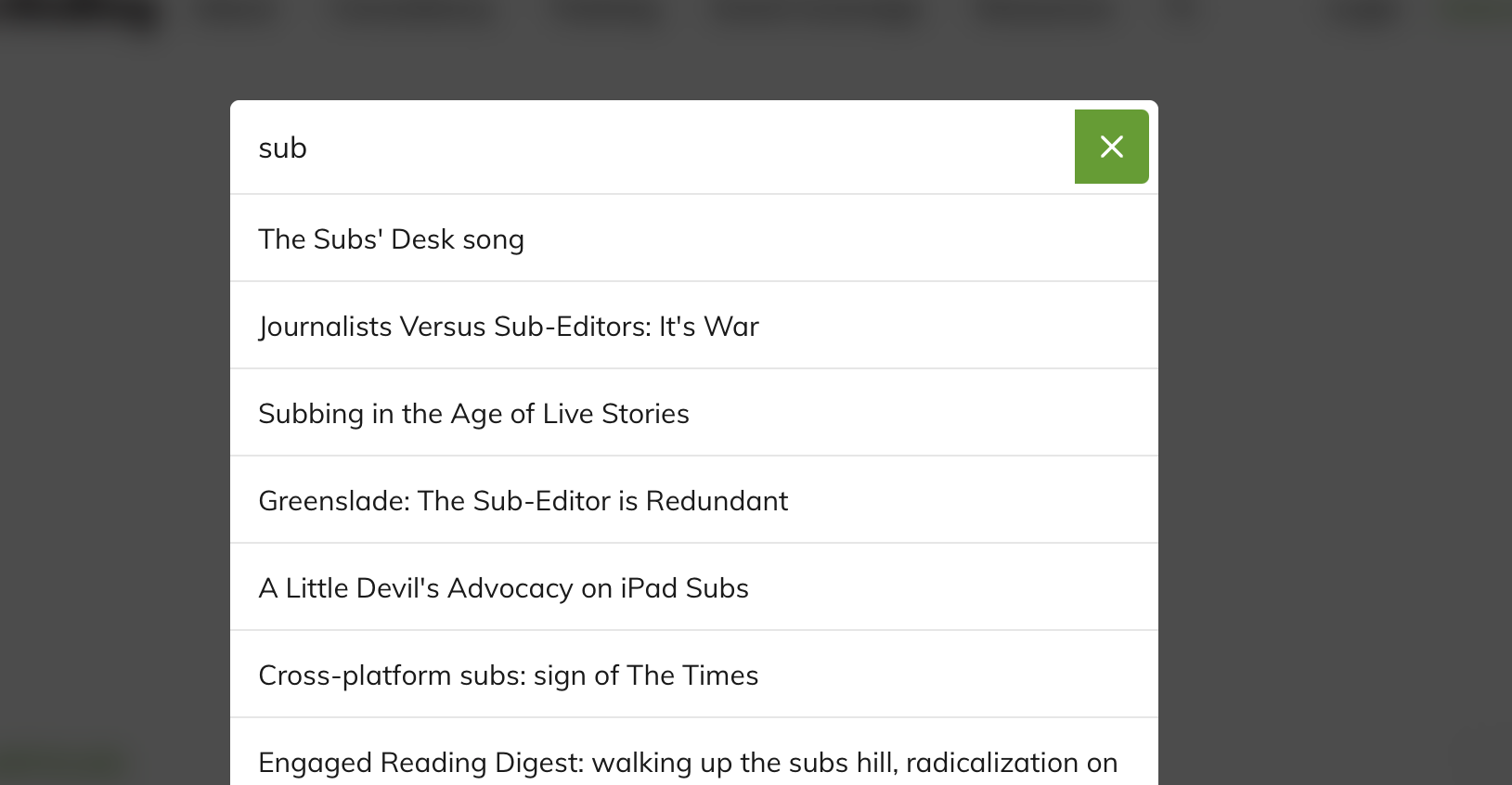

The search box up the top of the page is (finally) live. You can now search through 18 years' worth of posts whenever the mood takes you!

Quote(s) of the Day

Freddie deBoer (Substacker, controversial (funny how often those two go together), has done at least one Really Bad Thing, writes really interestingly) on the mainstream media backlash against the creator economy:

People who are not just not insiders but actively exiled are making a lot of money selling their opinions directly. Worse, precisely because of that bundling function of publications, many of those who are struggling to make ends meet with journalism careers do not have the kind of individual names that they could use to write independently. I think this drives much of the anti-Substack animosity, honestly.

This, from the same piece, is also an astute observation:

I would add that the endless use of tired phrases (“when you are not mad,” “the friends we made along the way,” “thank you for coming to my TED talk”) is not generally undertaken to actually amuse. It indicates in-group status; it aligns one with a particular tribe. But either way, the experience for the reader is the same: most everybody in media uses very similar humor in a way that shrinks the possibility for surprise, which is an essential element of something being funny. It’s all the same shit.

Thank you for coming to Freddie's TED talk. 😇