Report the Ukraine war – but give people an escape route from relentless horror

The war in Ukraine is understandably dominating the headlines. But can we report the conflict well and show empathy for readers?

Be warned: I’m about to commit what some people might regard as journalistic heresy.

It’s impossible to ignore the situation in the Ukraine right now. Like most other people, I’m watching the events there with a mix of horror and fear, and with support for the Ukrainian people fighting for their freedom. But, like so many others, there’s little I can actually do with that information. I can throw a little money their way. But beyond that? I’m not even a member of Anonymous.

There’s a problem with overwhelming people with frightening news that they can’t actually act on. And that’s what I want to talk about in today’s post. And then, for reasons I’ll get into below, we’ll move on to other topics for the rest of the week.

Times of crisis can’t be all about the crisis

The Ukrainian war is undoubtably a crisis. It’s brought us closer to a global war — and a nuclear one — than we’ve been in decades, and that’s some pretty scary shit right there. Numerous journalists are doing some great work reporting it — some at aignificant risk of losing their lives in the pursuit of truth. Even those sat safely at their desks outside Ukraine are having to process difficult, dark and often horrifying news.

I don't envy them — but I'm glad this vital work is being done, and generally done well. I’ve compiled some of the guidance that’s been published to help journalists reporting on it below.

But I want to discuss the rest of us. Those whose beat isn’t politics, or global diplomacy or war. The majority of journalists, in fact. Should we drop everything and focus on the war?

No. In fact, we need to continue on as we were before, both for ourselves and for our readers. Now is the time to prove that we’ve learnt one of the biggest lessons from the pandemic. Nobody — except, perhaps, a handful of journalists — can handle bad news constantly. And we’ve got a surfeit of bad news right about now.

Just as the pandemic was easing off in some parts of the world:

- Russia invaded the Ukraine

- The IPCC issued its bleakest warning yet on climate change

In an ordinary week, the latter of the two would be enough to dominate headlines on its own. But, thanks to the former, it will fall somewhere down the agenda. Imminent nuclear apocalypse beats out less imminent environmental catastrophe. There’s an argument that things should be the other way around, but with a notable exception, that news priority judgement call has been made.

This is very interesting (thx @andorand for the ht).

— Thomas Baekdal (@baekdal) February 28, 2022

NRK (National broadcaster in Norway) has been featuring three articles about the UN Climate report above the war in Ukraine:

Obviously the story about Ukraine is very important, but climate change is the bigger story. pic.twitter.com/tLPefE1wwn

These are not slow news days. This is more news than people can handle.

Twitter has been a bit harrowing for the last few days, as the algorithm seems to be ignoring anything that isn’t Ukraine-related. This feeling of impending apocalypse hanging over is deeply familiar to some of us.

Balancing awareness with the price of fear

Those of you of an age with me — and by that, I mean deep middle age — will remember the 70s and 80s, and growing up feeling that nuclear annihilation could be only hours away. It’s a damn shame we’re back in that territory after a couple of decades away from that fear. I really hoped my daughters would be able to grow up without it, but it is what it is.

You had, in the end, to push away the feeling that planning for the future was pointless because you could be dead in hours, and get on with life. There is no point in obsessing over something we can’t change and can’t impact.

Today, we’re bombarding readers with repeated stories about the danger we’re all in with little effective route to countering it. It’s a great way to create some serious mental health issues.

We already know that this feeling of a lack of agency has created mental health issues out of everything from Brexit to Climate Change. The return of an immanent threat of nuclear war will fall into the same category.

So, my fellow journalists, let’s not make that worse than it needs to be.

Routes to different stories

Let me be clear: I’m not arguing that there shouldn’t be very significant amounts of reporting on Ukraine, and that it should top the news agenda. It should. And that reporting must be done. It’s an inescapable reality of the war that there’s a major story out there that needs telling. As I said above, there are plenty of journalists doing that right now.

But those of us doing audience work, editorial priority work and who are designing homepages and newsletters, need to act with caution and empathy.

To push or not to push

In particular, those who hold the keys of push notifications and email alerts, have to think a little more deeply before pressing “send”. Is this a piece of news that people require shoved in their face right now?

Let’s look at two examples. This, from The Guardian:

Very much an “oh, shit” notification. Something very scary, with not much context — but, at least, a call to action for more information.

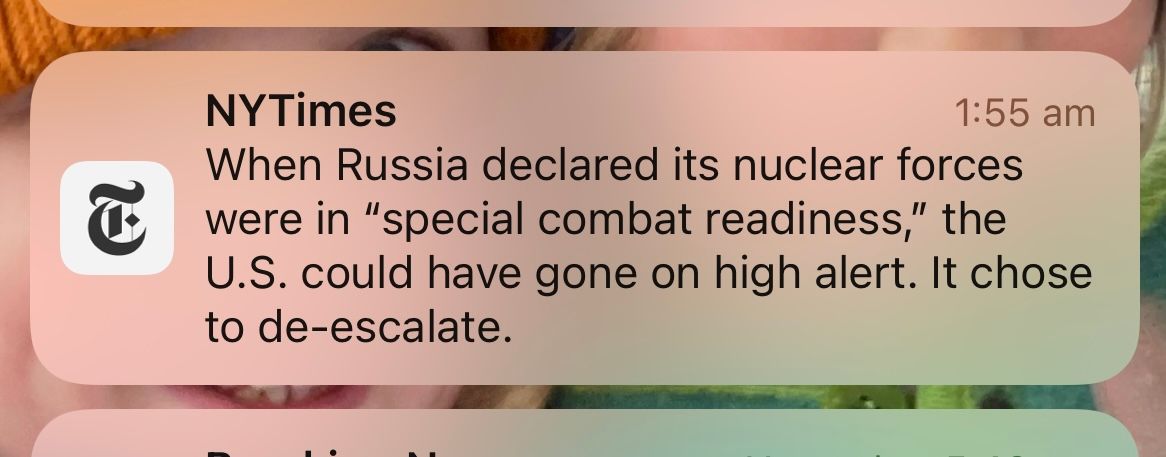

Compare with this from the New York Times:

Informative, clear and with less of an adrenaline-generating approach.

I’m not saying one is right and one is wrong — but I am saying that one will scare people more than the other. Now yes, scaring people generates traffic — but it also generates news avoidance, as we found out during the pandemic.

Balance your newsletters

How about newsletters? While I was writing this, an email arrived from The Telegraph. Chris Evans, the editor, highlighted six stories:

- Four about Ukraine

- One about the cost of living crisis

- One about spring day trips

That’s five relentlessly difficult stories, and one almost ridiculously fluffy story. (It involves lambs…). That’s not only making Ukraine all but the only story in town, it’s depriving journalists on the team working on other stories the chance for attention on their work at exactly the time that attention will be hard to come by. A spread of three Ukraine stories, two other serious stories (nothing on the IPCC, Chris?) and one lighter one would have made for a more audience-friendly balance.

Despite that habitual drive in the newsroom towards throwing everything at the kind of story with the enthusiasm of Chris Morris declaring “It’s war!”, we still need to keep our eye on all the rest of the news and information people need.

Build in escape routes

So, give people an option to switch to other stories.

If you’re a news publication, give readers clear routes to other parts of your site, rather than constantly pushing more variations of the Ukraine story at them. Make sure your recirculation links point to a range of stories, so you can keep people informed, without triggering news avoidance. Make it easy for them to take as much war coverage as they can manage — and then move on to other things.

If you’re a B2B or consumer publication, acknowledge the war where it impacts your readers, but carry on with the rest of your work. Don’t force references into your stories where they’re not needed. Remember, people can throw themselves into their jobs or their hobbies as a reminder that life is worth living, even in the face of existential threats.

Because, sometimes, giving people an escape is the most useful thing when news itself becomes nigh-inescapable.

Resources for those covering the war in Ukraine