Twitter, death threats and civility: rethinking journalism on social media

The platforms undoubtedly need to do more to deal with the toxic environment on social media. But it's worth considering our own role in stoking that febrile atmosphere.

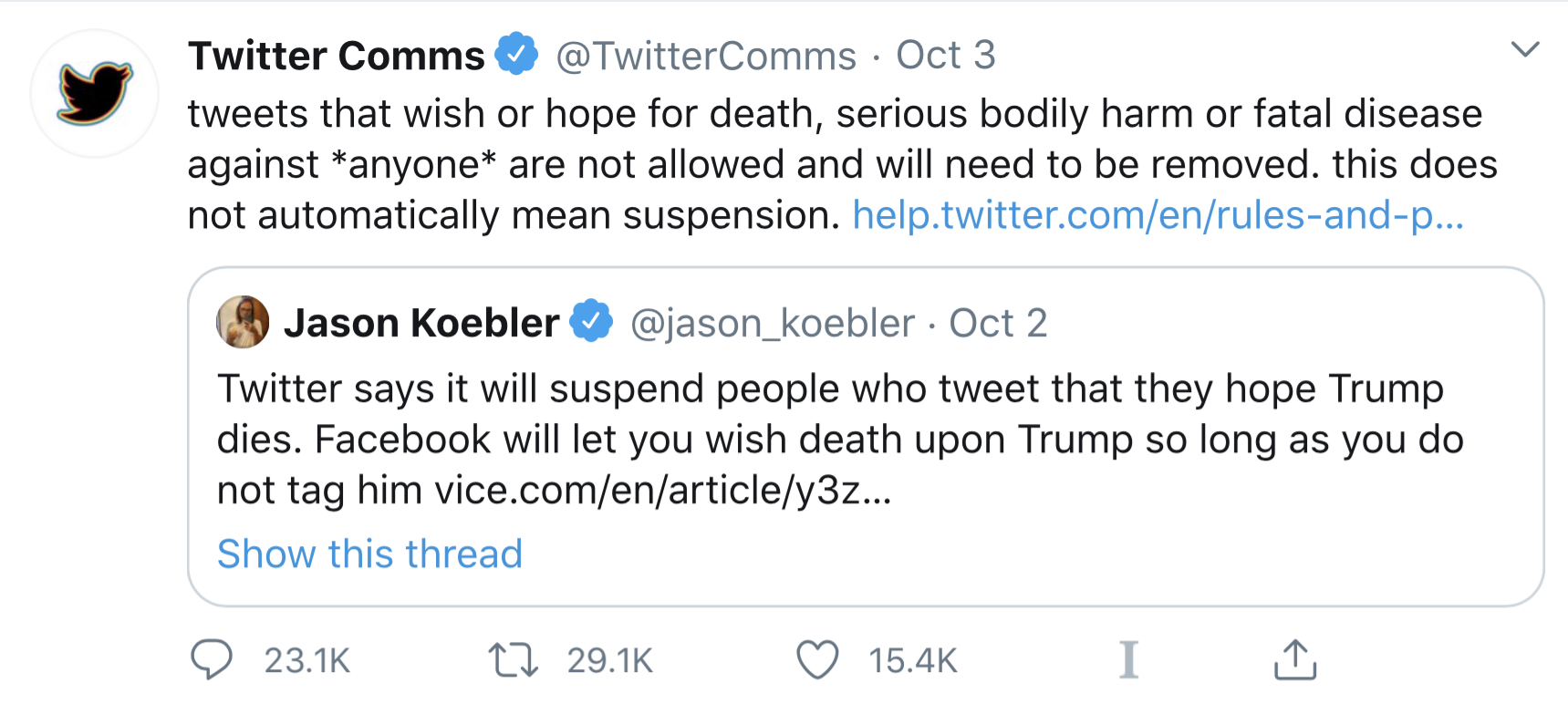

Twitter thinks celebrating the potential death of a president is a Bad Thing, and should lead to consequences for your account:

Which is all fine and lovely and perfectly sensible and clearly in the cause of more civilised debate online and should be welcomed…

Except, well, they’ve been allowing death threats on the service for (checks notes)… years?

You’re going to need to hire more staff because I and every other woman on this platform has a bit of a backlog for you. https://t.co/IR1viLsLcM

— Brianna Wu (@BriannaWu) October 3, 2020

Twitter would have got a lot more kudos for this announcement if it hadn’t taken the life-threatening illness of the most polarising US president in living memory to trigger it. An understandable backlash is underway.

Three tiers of Twitter users

It’s perhaps one of the most disappointing aspects of Twitter that it has moved from being a service that could amplify anyone’s voice, if they had interesting things to say, into one with a clearly hierarchical nature:

- We, the hoi polloi are at the bottom

- The “blue tick” verified users are a stratum above

- There are a handful of super-users, Trump included, around whom policy is made, and for whom existing rules are often ignored or altered.

So, good that they’re doing this, but excuse me (and pretty much the rest of journalism and politics Twitter) if we’re sceptical that this will actually make any difference to the threats received by anyone but the most prominent of users. Indeed, Twitter’s inconsistency on this policy is hardly new. It dates back at least six years.

Twitter needs to delete any death threat or similar reported to it, if it has any hope of clearing up the hell-site it has become. The challenges it faces, though, are ones of declining civility in online discourse.

Belam’s Big Box of hate mail

Martin Belam’s post from the weekend sums up the experience of many journalists who write about political stories, and whose social media profiles are easily discoverable:

I’ve been called a “simpleton”, an absolute shill for the Leftist mob, a moronic wanker, a fucking imbecile and someone signed off simply “you are an idiot”. Nice of the mother-in-law to get in touch, etc etc…

Someone else tracked down my personal Facebook to message me that my reporting and that of another journalist showed that we must be “spreading your assholes open for your boyfriends”.

One of the reasons I still tend to post most things I Have Opinions About to my blog, rather than Twitter, is that, while they’ll reach fewer people, they’ll be people with the intelligence and patience to engage with more in-depth issues, and consider nuance. And I don’t fancy death threats.

(Yes, this does mean that I’m contributing to the spiral of silence.)

Blogging is hardly perfect, but because it takes more effort to do than to fling your brain meats onto Twitter or Facebook, it tends to promote slower, more measured debate. And that means that the quick mob mentality social effects don't kick in nearly as easily.

Which does rather force us to conder why the profession wrote off these slower forms for the quick hit of social media reinforcement so very quickly.

Journalism’s corruption of blogging

On Friday, I felt an old anger, one that hasn’t been stoked in me for ages, when I came across this piece of nonsense on a journalism site looking at the rise of newsletters:

The reason no one talks about “blogging” anymore is that, for what blogs were good at — sending your personal views on the news (or some other topic) to a dedicated audience — other tools offered simpler, more effective tools for doing just that, most notably social networks. Why go through the trouble of setting up your own blog and slogging through a cumbersome back-end CMS when you can just create an account on Twitter and start sharing hot takes in a couple of minutes?

I could easily devote a whole post to a good, old-fashioned fisking of this piece, but, really, who has the time? The key problem here is Pete Pachal’s equation of blogs with “sharing hot takes”. That manages to do two things which he, presumably, did not intend to do:

- Shows up how little he understood the blogosphere that was (and the blogosphere that is)

- Shows exactly how Twitter went bad. When journalists with big followings slide over there to share their spicy hot take, nothing but polarisation emerges.

Opinions are over-rated

Speed and quality are not easy bedfellows, and when you create environments that promote both speed and a lack of nuance, you create a hostile polarised environment. The old days of blogging did encourage speed, but they also allowed for nuance and, critically, opened you to the possibility of error.

This was a good thing: being open to your ideas being proved wrong through challenge and debate is the sign of a civilised and open mind. Here’s Andrew Sullivan quoting Ezra Klein on his post-blogging journalistic career:

It’s harder and harder to learn; harder and harder to be wrong. And I worry that the end result of that is getting really bad at the job. … I miss the idea in blogging that you could be wrong, that you could be uncertain.

(Quote is from an episode of the Ezra Klein Show, which is a routinely excellent listen.)

Let’s rewind 15 years, to when I was establishing myself as head of blogging for a business publisher. One of my key insights then was that writing a blog did not equate to suddenly having your own opinion column. A blog was there to be useful — to share more casually interesting things with your readers as a supplement to your mainstream reporting, not a replacement for it.

It’s better to be useful than opinionated

If you are going to express opinion, rather than add context, then make sure you have something valuable to add, and that you have some genuine level of expertise. (The traffic figures on the opinion-centric blog posts of journalists fresh to a particular beat when compared to their more experienced colleagues was instructive on this point.)

Instead, bias your work towards being useful. Share good links, give insight into news, draw connections between disparate sources. Make links, and help the reader navigate an ever-expanding information ecosystem.

Twitter, at its best, still functions in that way:

- here’s an interesting link

- here’s a useful fact

- here's some missing context

- here’s a fun moment from my life

That sense of a fun interplay between useful and social is what makes the dynamic work. But, in terms of platform or follower growth, it doesn’t have a patch on heading over there and vomiting your spicy hot take on the world.

Resist the lure of the hot take

The problem is the more we, as journalists or other communications professionals, participate in and reward that behaviour, the more we normalise it in others.

I fight this battle in myself. You might catch a glimpse of just such an internal battle I’ve been fighting in my post from earlier.

In this context, I’m less hostile to initiatives like the one underway at the BBC than many are. Journalism has strayed too far into the wilds of opinion and partisan behaviour. We need to navigate our way back to a more useful position, without losing that sense of openness and transparency that social media has, at times, brought to our profession.

It’s easy to blame the platforms for the increased polarisation of our debate. And they should be shouldering much of the blame. We do, though, need to assess our own role in driving this abandonment of civility, and think how we might regain…

…the high ground.

A public notebook

Talking of blog as notebook, I’m trying a wee experiment with Substack this week. I’m sending out daily emails that are, more-or-less, my notebook and thoughts in public. Very old school blogging. Now, if you’re getting this via email, you probably don’t want even more of me in your in-box, but just in case, you can go subscribe here:

Not sure how long the experiment will last. I’m not a fan of SubStack’s interface, and I’m not good at following through side-projects on platforms I don’t enjoy, but I figure I need to be more familiar with its mechanics, so an experiment is justified.

Sign up for e-mail updates

Join the newsletter to receive the latest posts in your inbox.