Meta pirated books — and trained AI on them.

And it looks like some of mine were in there.

Somewhere, deep in Meta’s AI models, there’s a good chance that there are patterns learned from my creativity. But more than that, in the same data hoard are patterns learned from my wife and my sister-in-law’s research. And Meta paid not a penny to any of us – or to the publishers who put out those books and academic papers.

How do I know this? I typed my surname into the search engine The Atlantic created to show what books are in LibGen, the pirated books store that Meta used to train its AI model.

The advantage of having an unusual surname, is that it’s easy to find the family in the results. A search for “Tinworth” throws up 49 results:

Tinworths as authors in LibGen

| Tinworth | Number of publications |

|---|---|

| Kellie | 15 |

| Adam (me) | 11 |

| Lorna (my wife) | 10 |

| H | 4 |

| Christopher | 3 |

| S | 2 |

| Joanna (my sister-in-law) | 1 |

| Sue | 1 |

| Kathleen | 1 |

| D | 1 |

Although my wife seems behind me on this list, she’s actually ahead: there’s at least two papers she co-authored under her maiden name in there, too. If you’re interested, none of the books attributed to me are journalistic – they’re all from my days writing TTRPG books a couple of decades ago. (Check out most of my Wikipedia entry for details.)

A product built on uncompensated labour

What this does mean is that my family’s labour has been used as part of Meta’s new LLM product, without any recompense. And they clearly knew this was the case, as The Atlantic’s reporting make clear:

Meta employees spoke with multiple companies about licensing books and research papers, but they weren’t thrilled with their options. This “seems unreasonably expensive,” wrote one research scientist on an internal company chat, in reference to one potential deal, according to court records.

And:

In a message found in another legal filing, a director of engineering noted another downside to this approach: “The problem is that people don’t realize that if we license one single book, we won’t be able to lean into fair use strategy,” a reference to a possible legal defense for using copyrighted books to train AI.

Now, is this a bad thing? Possibly not. I’m certainly amenable to the argument that using publications like this does count as fair use: LLMs are a derivative work of the original content, not a straight copy.

Does it sting that Meta, a company of vast wealth, didn’t even pay for individual copies of the works it trained, choosing to use a pirate dataset instead? Yes, of course. That’s just cheap — and it betrays a deep sense of entitlement to the work of others. But the fundamental legal case remains untested, although that’s sure to change. For example, the Society of Authors is actively looking to get recompense for its members.

The liminal space of AI copyright and use

Let’s be honest: nobody really knows how this is going to pan out. Yes, there’s a wave of AI “gurus” out there, but most of them were metaverse gurus 10 minutes ago, and blockchain gurus 15 minutes before that. Some of them date right back to the Web 2.0 gurus of 20 years ago, and have never found a technology bandwagon they won’t ride until the grift runs out. I think we can safely ignore their bullshit.

We don’t know exactly how AI will be used. We don’t know what the legal structures around it will look like. And so, we’re in unexplored territory here, and the best strategy is to keep talking to each other to figure out how to make the most of this tech, while minimising the potential harm. If the last 20 years has taught us anything, it is that “minimising harms” needs to be as important as “maximising benefits”.

As I’ve been exploring recently, AI is an emergent and transformative technology we haven’t really figured out the use cases for yet. But we will. But, while that process happens, we’re left with difficult choices.

For example, should you block AIs from crawling your online content?

To block or not to block

If you’re a big publisher, the answer is probably “yes”. You have a good chance of being able to strike a deal with the AI companies to get some money – and possibly access to technology – in return for your content.

For small, indie and individual publishers – like myself – that’s a more challenging question. Unless we band together in some way and exert collective bargaining power, we’re never going to be able to extract cash from the big AI companies. So, for us – for me – the question is: should I block AIs from training on my content, knowing they’ll never recompense me for that, or do I allow it, on the chance that their service will send traffic my way?

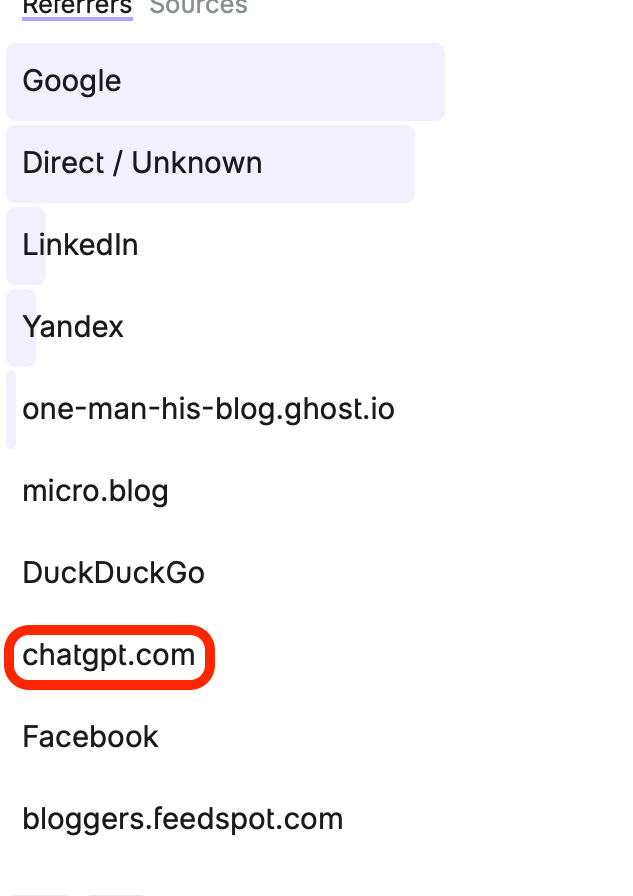

I’m starting to get a little bit of traffic from ChatGPT, for example. Here’s the list of rearers to my site over the last month, in decreasing size:

As you can see, there’s traffic — but it’s a tiny fraction of what I get from Google right now.

One Man’s decision on blocking AI crawlers

For now, I’m choosing not to block, but keeping a watching brief. I think what I’m offering here – analysis, opinion, and aggregation from somebody with two decades studying this stuff – is not directly susceptible to attack by AI. In essence, you’ll become a reader, a subscriber, and maybe even a site supporter, if you trust me. And if you’re the sort of person who would rather get that from an over-confident guessing machine, then you’re probably not my target audience.

I am tempted to block Meta’s crawler, just out of spite. I don’t like the company, I have never liked the company, and every year that goes past proves my initial impressions correct.

To go back to that Atlantic piece:

Meta employees acknowledged in their internal communications that training Llama on LibGen presented a “medium-high legal risk,” and discussed a variety of “mitigations” to mask their activity. One employee recommended that developers “remove data clearly marked as pirated/stolen” and “do not externally cite the use of any training data including LibGen.” Another discussed removing any line containing ISBN, Copyright, ©, All rights reserved. A Llama-team senior manager suggested fine-tuning Llama to “refuse to answer queries like: ‘reproduce the first three pages of “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.”’” One employee remarked that “torrenting from a corporate laptop doesn’t feel right.”

This is not a company with respect for the law or other creatives.

The longer-term danger to AI companies

Here’s where I worry, though. The AI companies are in serious danger of biting the hand that feeds them. Just think though the scenario that’s already playing out:

- Companies train LLMs on online and digital content for free

- Companies build paid products that supplant the sources of the original data for a significant number of people

- The companies producing the original data’s business models collapse, and so they stop creating new content

- What the fuck do AI companies train their models on now?

There is a symbiotic relationship to be had here – but the AI companies are too rooted in the old mindset of Silicon Valley creative destruction and a failure to work about the consequences of their actions to create it. They either need to support the publishers whose work they're using – or think seriously about their products, and how much risk there is that they will choke off the flow of training material they need.

Rough times ahead, for all concerned.