It’s time to stop embedding tweets in news stories

The possibility of an Elon Musk-run Twitter has people heading for the doors. If we see a mass deletion of accounts, all of a sudden a lot of news stories while find crucial embedded elements at risk.

It is slightly bizarre to think that, by the time I press publish on this post, Elon Musk might own Twitter. I’m not going to join the legion of people claiming they will quit Twitter if that happens. I’ve been on the platform for over 15 years, and have seen plenty of drama come and go. I'll stick around with some popcorn, and watch him repeat the mistakes of the past.

The odds of anyone with a blue tick and a very substantial following actually, truly deleting their Twitter account should Twitter be Musked must be astronomically small. A habit like that is terribly hard to kick.

— Adam Tinworth (@adders) April 25, 2022

But there will be some consequential risk for those of us who embed tweets in articles, like I just did right above this paragraph, if others do both quit AND delete their accounts.

The rules of embedding

The rules have always been pretty simple: you should, wherever possible, use tweet embeds rather than screenshots of tweets. Of course, you should keep a screenshot of the tweet if you think there’s a serious risk of the originator deleting their tweet, and it’s a critical part of the story.

The exception is, of course, outlets who tend to attract enough opprobrium that people will change their usernames to obscenities, if they find that they’ve been embedded in an article on, oh, say, MailOnline. They go straight to the screenshot to minimise that risk.

However, for the rest of us, the screenshots weren’t strictly necessary, as the embeds gracefully fell back into blockquotes. So, this:

Rule No. 1 about leaving Twitter: If you feel compelled to tweet about leaving, you're probably not leaving

— Alex Kantrowitz (@Kantrowitz) April 25, 2022

Would become this, should Alex leave the platform and delete his account:

Rule No. 1 about leaving Twitter: If you feel compelled to tweet about leaving, you're probably not leaving

— Alex Kantrowitz (@Kantrowitz) April 25, 2022

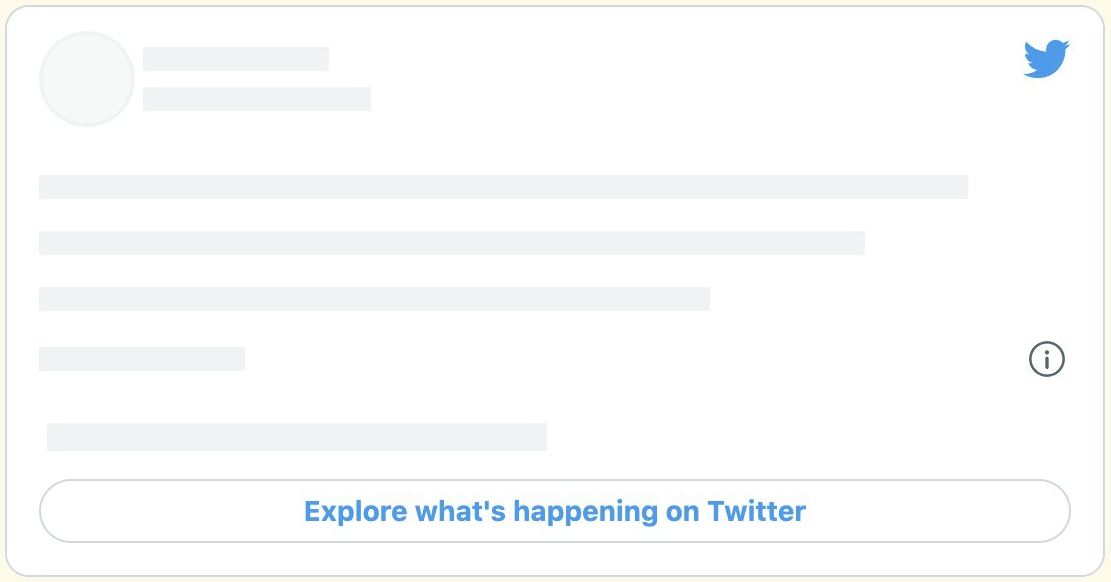

However, as noted by Kevin Marks earlier this month, this recently changed. For a while, an embedded tweet that’s been deleted looked like this:

That’s a significant regression in the usefulness of embeds in journalism. The words you’re quoting are no longer available to the reader. They might well still be in the source of the page, but the javascript at work is obscuring them. You could go in and edit the embed source HTML to create the older quote effect demonstrated above — but that's slightly technical and presupposes that you're aware the tweet is gone.

In effect, those publications who have done the right thing — embedding — rather than the wrong thing — screenshooting — looked like they were being penalised for it.

Why did Twitter do this?

Kevin was able to winkle an explanation out of Twitter:

Hey Kevin! We're doing this to better respect when people have chosen to delete their Tweets. Very soon it'll have better messaging that explains why the content is no longer available :) my DMs are open if you'd like to chat more about this

— Eleanor Harding (@tweetanor) March 29, 2022

And yes, that does make sense. But it also had the effect of breaking all sorts of news stories, not least the ridiculously large number of articles from the late 2010s based on the tweets of one now-ex-president Donald J Trump. However much you might despise the man, there’s no doubt that his tweeting was part of the historical record of the era, and that’s now getting ever harder to access.

However, thankfully, for the time being, Twitter has reverted to the old behaviour:

“After considering the feedback we heard, we’re rolling back this change for now while we explore different options,” Twitter spokesperson Remi Duhé said in an emailed statement to The Verge. “We appreciate those who shared their points of view — your feedback helps us make Twitter better.”

They're still exploring “different options”, though, and they're rolling back the change “for now”, so change is probably still coming (Musk allowing). And this is a sobering reminder that, when you embed something on your site, you lose control of that element of your page.

So, what do we do?

It’s worth considering changing your house style to quoting Tweets rather than embedding them. So, in effect, you treat something on Twitter like anything else you want to quote from the web: use the text in the body of your article, in inverted commas or in a blockquote, and then link to the original source.

So, for example, I could take Kate’s tweet:

comment pages are just endlessly bloody recycling the current outrages. "My hot take on why yesterday's bad thing is bad."

— Kate Bevan 🇺🇦 (@katebevan) April 25, 2022

And just render it thus:

comment pages are just endlessly bloody recycling the current outrages. "My hot take on why yesterday's bad thing is bad."

That's all on my server, so if Kate does choose to delete her tweet, my story still makes sense, whatever Twitter decides to do.

If it’s anything mildly controversial, I’d also keep a backup screenshot, just in case it was needed as evidence of the original tweet. But with a tweet like the above, no need.

The risk of embeds

Embedding content in your site is always risky, especially when it’s critical to the story. You are, in effect, extruding a bit of that platform into your site. And with that extrusion comes the risk of the content changing in ways beyond your control, as well as allowing little elements of the tracking that these platforms use onto your pages.

I’m going to be quoting more and embedding less here in future. Yes, that does mean I’ll have to put a little more effort into breaking up text into readable chunks, and generally making my pages look pretty. The quick visual hit of a pretty embed is something I'm going to be less trusting off in future. But the trade-off for that is content whose future I control, faster page loads times and less tracking of you, dear reader.

It’s time to consider if that’s the right approach for you and your site, too.

Sign up for e-mail updates

Join the newsletter to receive the latest posts in your inbox.