Digital News Report 2020: the trust crisis and its solutions

2020's edition of the Reuters Institute Digital News Report is dominated, as you would expect, with the changes wrought by the pandemic. But there's an underlying trends that's worth focusing on.

In the middle of the strangeness that is the pandemic, a little touch of normalcy: The Reuters Digital News Report 2020 is out this morning, and available for download. Of course, some things are different. A year ago, I was on my way to London for a panel discussion on it at Edelman’s offices. Today, I’ll be Zooming into a webinar, instead.

And, I must confess, this will not be quite my normal deep dive into it. While they were kind enough to provide me with an advance copy, homeschooling has deeply eaten into my available time, so my analysis is likely to be spread over a number of days. And there’s much to explore. For example, the shift in consumption patterns and collapse in revenue around the pandemic are both fascinating, and important. I do want to dive into them. And I will certainly return to the issues around subscriptions.

However, I suspect everyone else, will to. I've been listening to the webinar discussion while finishing this, and that has certainly been the focus so far. I'd like to go a different direction. There is one thread that leapt out at me, and one I want to take a little time to dive into now.

The News Metamorphosis

More than anything else, I take away from it an overwhelming sense that the industry is in mid-metamorphosis, one that is likely to be accelerated by the Covid-19 crisis, but is less aware of that than it should be. In particular, it remains focused on the idea of packages - particularly print newspapers - while not really facing up to the fact that the vast majority of people do not consume their news that way.

Instead, most people are accessing their news through feeds. When people encounter atomised content that way, floating free of its context on the web, they react to it in isolation, rather than as part of a package of reporting — or opinion. As the most controversial and, in some cases, most egregious, examples spread more readily on social media, that reshapes the perception of a whole industry.

But first the good news.

The trust problem is deepening

This is, I think, a telling result:

Across the sample as a whole, politicians are — quite rightly — seen as a much more concerning source of misinformation than journalists. (It is worth noting that the role of foreign governments seems to be being underestimated here, so we shouldn’t assume that people’s perceptions match well with reality.) It sometimes feels that very few people trust the press, especially if you spend extensive time of social media. But this is a useful reminder that the loudest voices do not necessarily match well with the majority viewpoint. The hardcore berating us for questioning our politicians almost certainly do not represent the majority view.

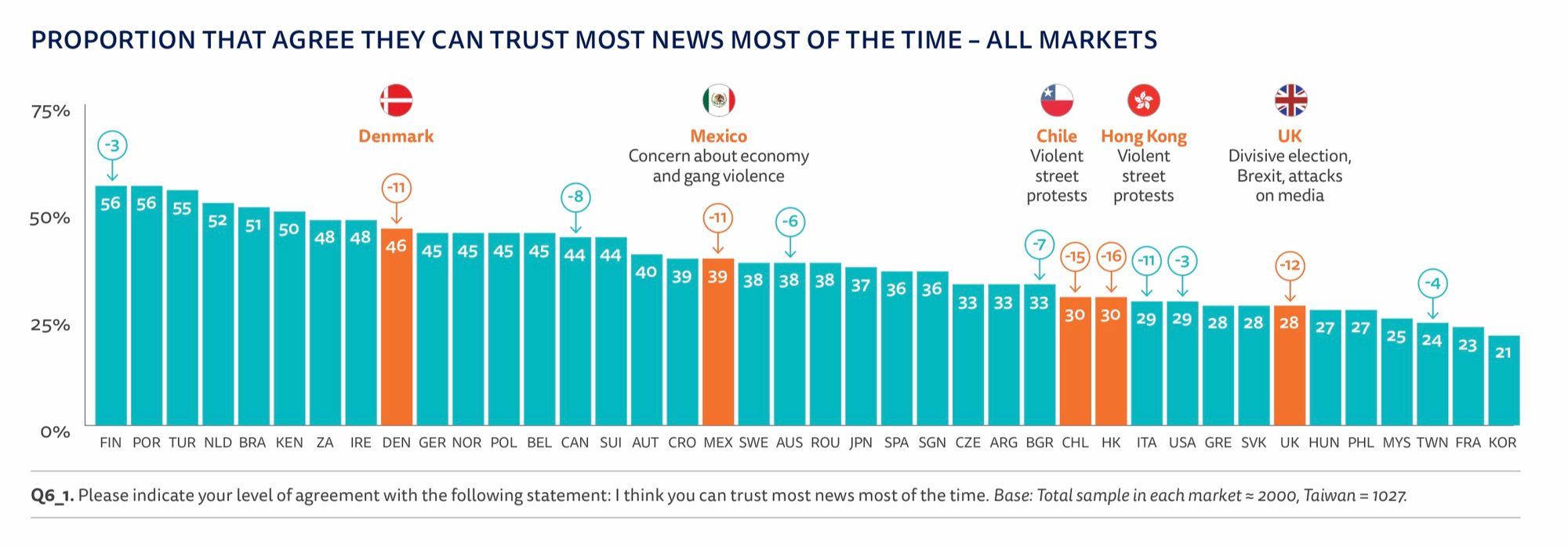

OK. That’s the good news. Here’s the rest of it. The picture on trust does not look quite so rosy in the countries most riven by polarisation. General trust in the media in the UK is not high:

Alarmingly, we’re below even the US, after the highly divisive five years it’s just been through. So, just because people think politicians are the major source of misinformation doesn’t mean that they trust us. Indeed, that major distrust seems to be a global issue, that we, as an industry need to be doing far better on. Only 5 countries pass the 50% trust level? That’s really not good.

But when you dig deeper on the UK’s trust problem, it just gets worse and worse.

The UK’s specific trust issues

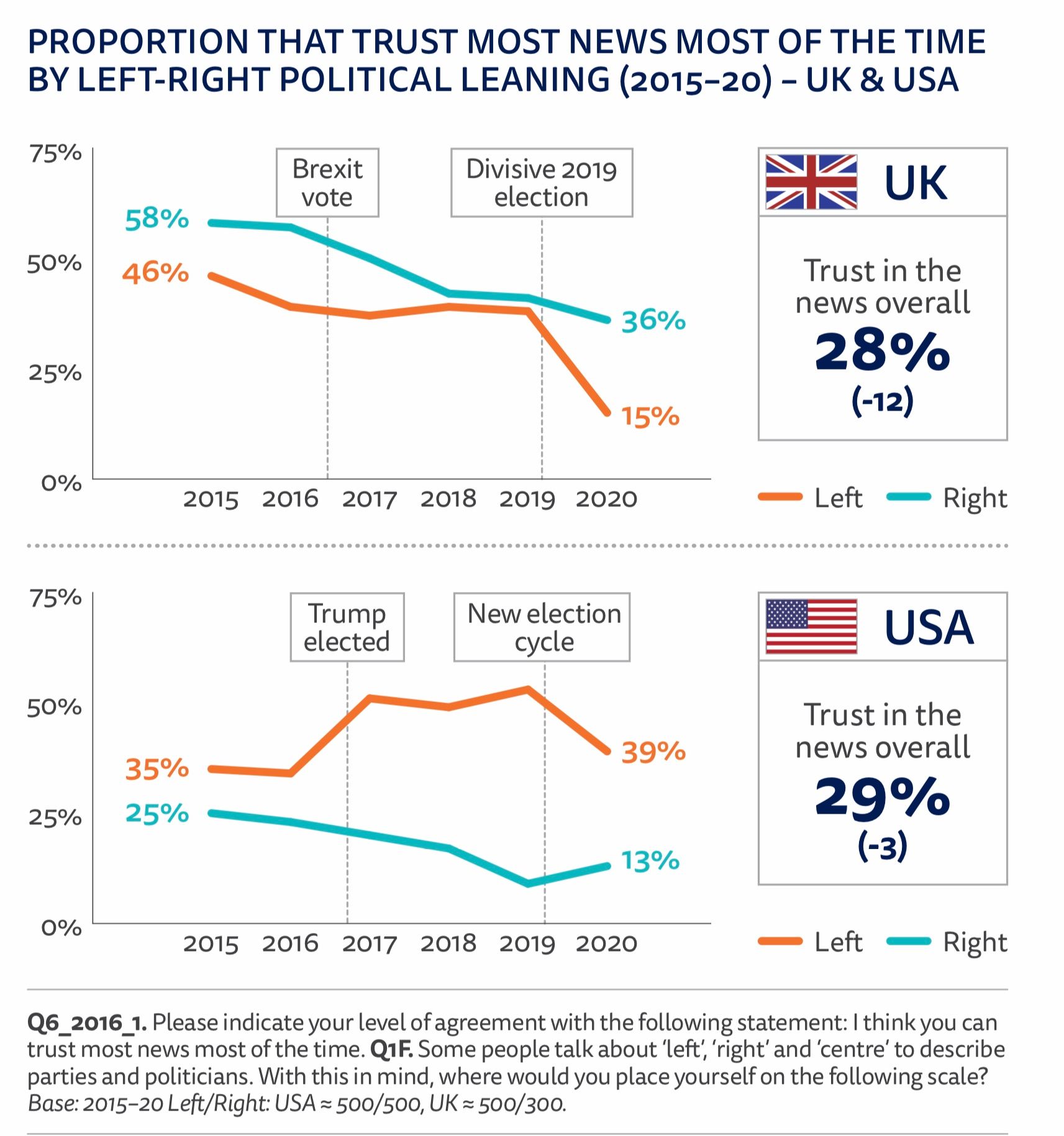

Trust in the media is not just low in the UK - it’s declining across the political spectrum.

The fall over the last five years is staggering. More than half of those on the right trusted the media in 2015, and even 48% of those on the left. The left’s trust has collapsed catastrophically since then, down at an embarrassing 15%, while the the right’s trust is also declining, down at 36%. It’s notable that the UK Conservative Party have stepped up their attacks on the media over that time, and the criticism from the left has only increased. When both our main parties are telling the public that the media are not be trusted, this is a predictable outcome.

These are truly alarming figures - and you are forced to wonder if the mainstream of journalism in the UK, still focused on the main newspaper brands - and the newspapers themselves - is capable of evolving in a way that could reverse this decline. We seem unwilling to truly let go of our old vision of journalism and embrace the reality of what's happening around us.

The Print Paradox

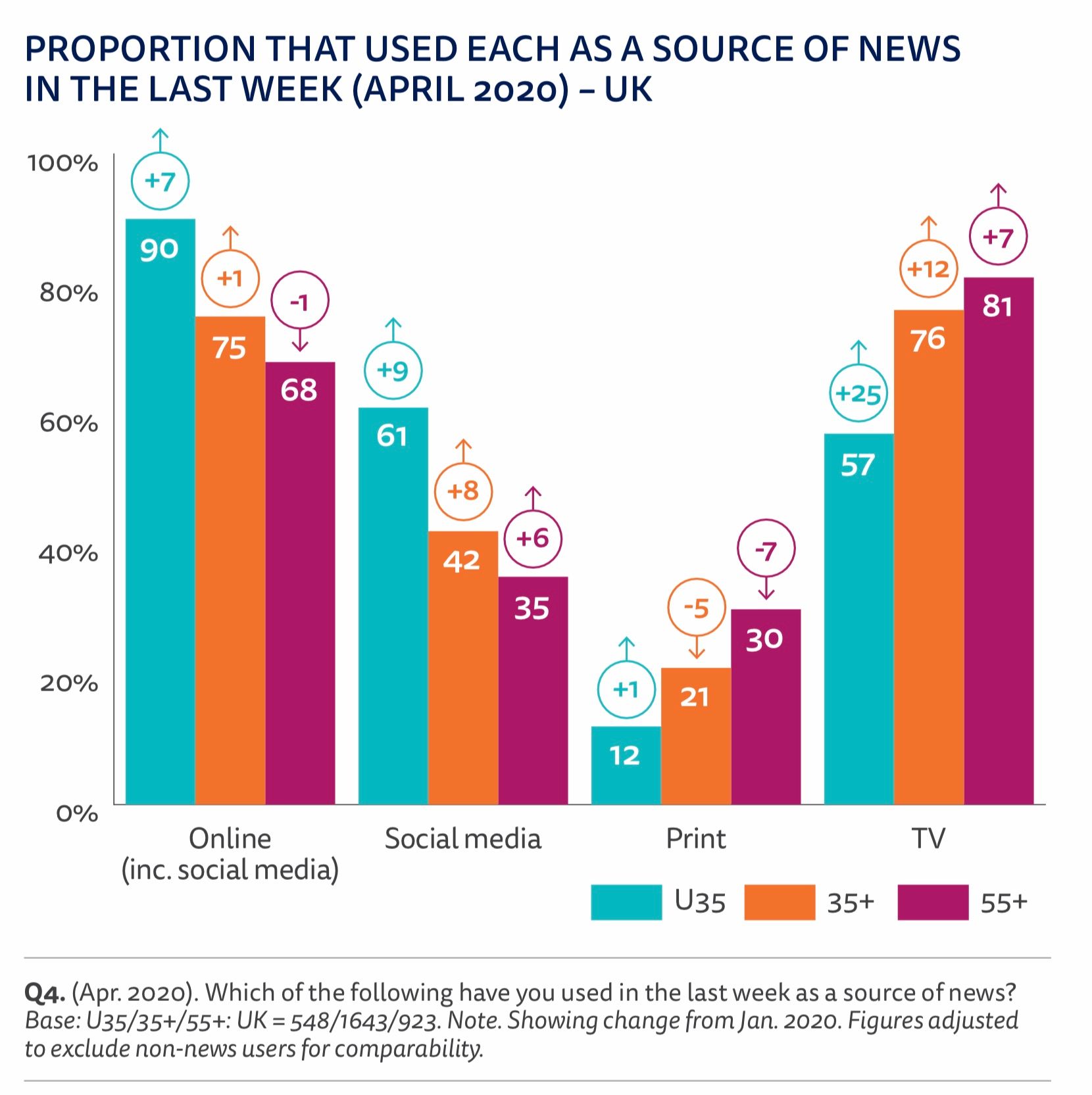

The UK journalism business remains strangely obsessed by paper. TV news still makes a big thing of the next day’s front pages. But the buying public? They’re not so keen, even with the proviso that the research is conducted online, and so will tend to under-represent the diminishing number of people who are not wired to the internet, and one has to wonder if three months of lockdown has broken the print habit in even more readers. As this graph shows, print newspapers are now the most marginal source of news source of news:

Only just over 1 in 10 of under-35 years olds use them, and even amongst the 55+ group, it’s only 30%. Print isn’t dead, but it’s very much a minority sport. Online is where the action is, with broadcast the strongest challenger - and even those figure are somewhat distorted by the clear surge un TV watching during the pandemic.

Now, it’s worth baring in mind that part of this focus is driven by the economics, with print still delivering a significant source of revenue. And, equally, the print reader is often one of the most engaged readers, so deserve focus. But equally, it’s hard to look at the demographic shift in print consumption and think it has much future.

It’s clear that the journalism business is obsessed by newsprint in a way that the public just isn’t. And that means we’re not waking up to some of the bigger threats - like the role of both social media and the aggregators in breaking the connection between the publisher and the individual news story.

Broken relationship links

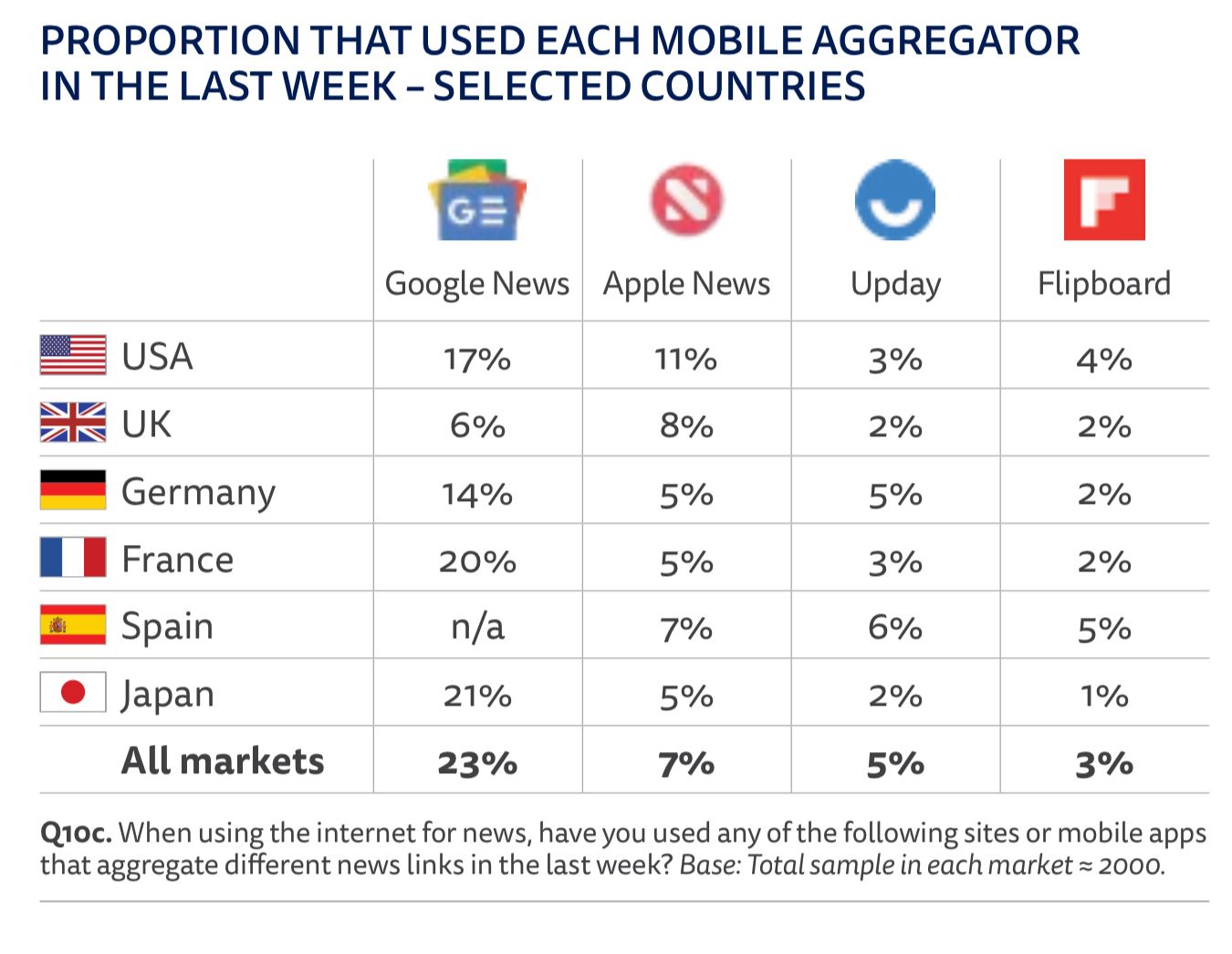

Use of the aggregators is on the rise.

Between that and social media, we are seeing people develop a relationship with the intermediaries — be they the social media platforms or the aggregators — rather than the titles themselves.

As I noted above, this atomisation of content is almost certainly fueling the distrust. People are only seeing elements of a title’s reporting. They have no experience of a daily encounter with a particular set of journalists’ reporting. They become interchangeable commodities, to be judged by the poorest of their output, not the best.

How on earth do we come back from this?

Re-engaging readers

There is a little hope buried in the report. Subscriptions continue to grow - which is encouraging, because it may well help curb the excesses of the clickbait culture that ad-driven media encourages. And as publishers pivot towards subscriptions, they commit more deeply to engagement-building tools that help maintain and nourish the relationship with subscribers - and hopefully reduce churn.

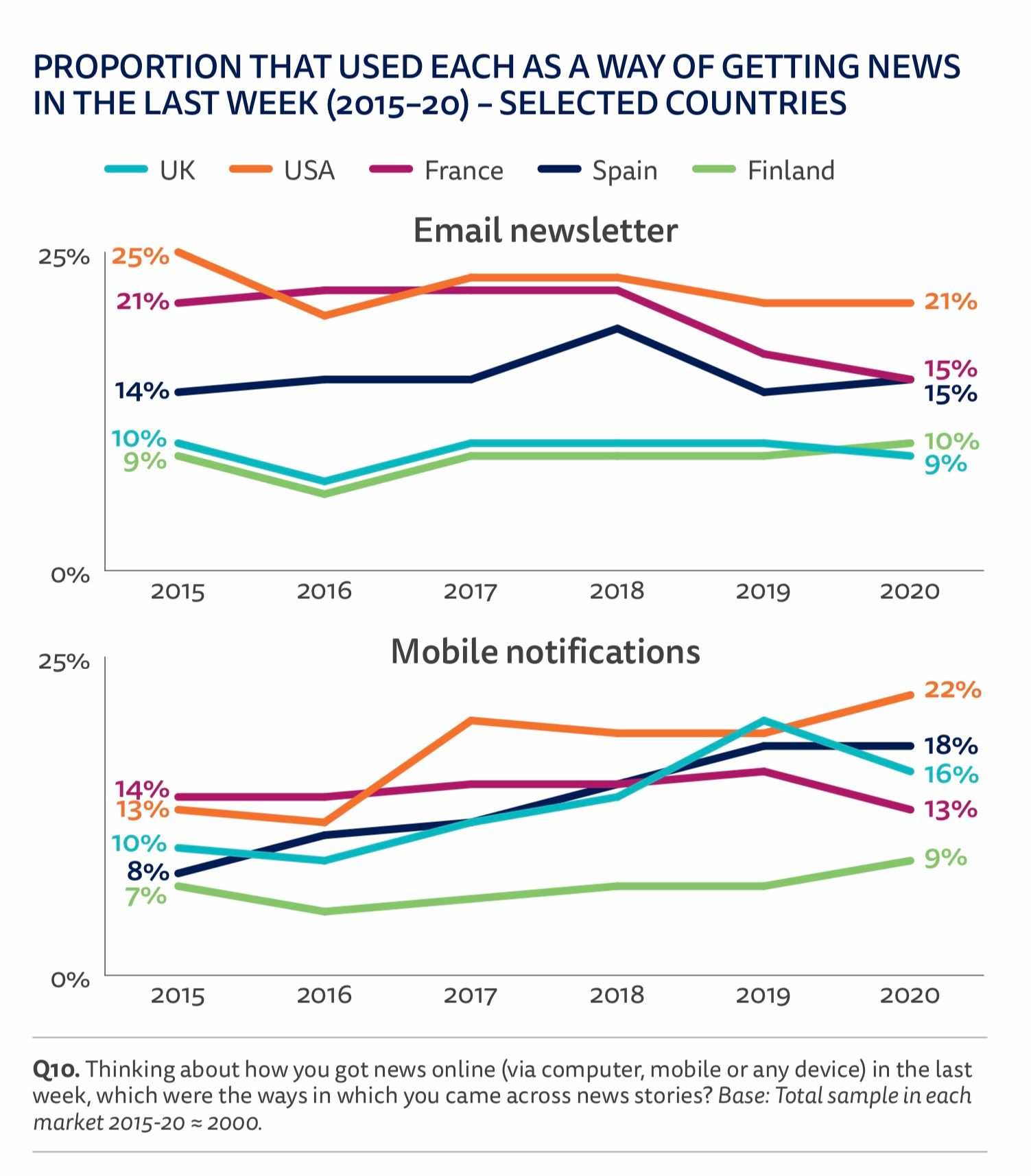

For example, the rise of both podcasts and newsletters as direct relationship-building tools is acknowledged in the report.

Here’s my take-away: I find myself wondering if we need to start changing the way we view things like newsletters and podcasts. They’re still seen in many newsrooms as essentially promotional tools, part of an audience engagement strategy, which helps readers discover the main site.

But what if they’re not?

What if they’re some of the delivery mechanisms of the future? What’s notable about both newsletters and podcasts is they’re contained, formats that you can finish. They both deliver that feeling of having completed something, having caught up, of being informed in a way that the web itself cannot manage.

Are newsletters, for example, in essence the newspapers of the future?

Perhaps. But there’s some challenges on that path.

Stalled growth

The proportion of people getting news from newsletters seems quite stable. If anything, there’s been a small dip in people, during this period of newsletter renaissance.

Yet, I know for a fact that some publishers are doing every well indeed out of their newsletters. So, there are some underlying questions here about wether the number of people using them is roughly stable, but they’re getting a better experience from them. Or wether the less than universal embrace of newsletters as a critical format of news distribution if curtailing their growth.

As Nic Newman writes in the appendix on newsletters:

Email news is no silver bullet solution. It is still a minority activity that appeals mostly to older readers and the format can be restrictive. But despite its relative unsophistication, it does remain one of the most important tools available to publishers for building habit and attracting the type of customers that can help with monetisation (subscription or advertising).

No silver bullets

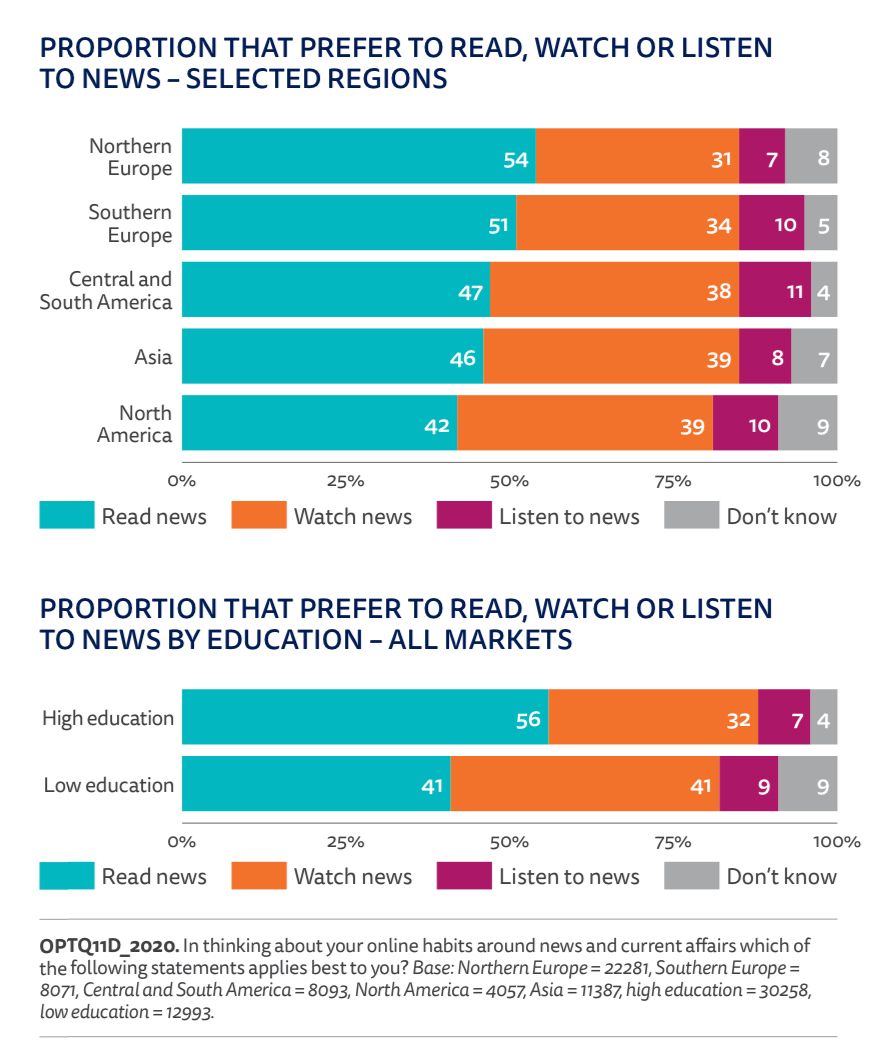

Perhaps, more importantly, it’s worth remembering that we’re almost certainly not going to see one approach replace the newspaper as the central means of discovery.

This chart of the balance of news media consumption preference is interesting:

I suspect that very few news organisations have a balance of out put that aligns very well with that desire line.

We still largely produce text-and-pictures - at least those of us in organisatiosn with a print background. We’re getting better at audio. But the UK, in particular, is still underweight in video. We’ve not seen any title over here have a real knock-out, YouTube success with video that, say Vox has in the US.

(I could get into a long digression here about how the blame for some of that might well lie, indirectly, with the BBC, with its news format being so influential on the industry, we struggle to escape it and explore truly digital approaches to storytelling. But I won’t. Because I have to start homeschooling my children shortly.)

But the common factor of newsletters, podcasts and video is that they allow us to spend extended periods with a single voice - or small groups of voices. You get to learn about the diversity of their work, and see different perspectives. You develop relationship, and within relationship grows trust.

The days of the daily newspaper dropping on your doormat, or picked up at the station on your commute (commuting - do you remember that…?) are unlikely to come back. We clearly need to find digital methods of creating that regular, and content diverse presence in people's lives. And that seems to mean getting more serious in delivering a diversity of 0utput types.

To me, the hidden message at the heart of this year’s report, distorted as it is by the impact of the pandemic, is a desperate need for us to focus more deeply on emerging formats, and on engaged journalism.

If we don’t, the twin poles of rising distrust, and the atomisation of the aggregators, will tear far too many news organisations apart.

Sign up for e-mail updates

Join the newsletter to receive the latest posts in your inbox.