Why the Streisand effect could hit The Times’s bottom line

The Times pulling a story about the prime minister shows a strange mix of deference to authority, and a disregard for its paying members. And that could be bad for subs numbers.

Journalism publishers are not good at hanging onto institutional knowledge. People come and go, and sometimes skills or understanding go with them. And the interplay between The Times and the government over the past week has been a perfect example of that. The newspaper has made an odd decision, and one that’s caused a storm of controversy that might actually impact the paper’s bottom line.

Through pulling a story about Boris Johnson trying to get a government job for his now-wife back when he was Foreign Secretary, The Times and, by extension, the government, fall foul of the Streisand Effect. A few pieces mentioned this in passing, including The Guardian’s. For those who are unaware, it’s a name for the way that attempting to censor anything in the internet age tends to have the effect of calling attention to it.

The BBC did an excellent explainer on it a decade ago.

The origin of the Streisand effect

It was named 17 years ago (when did I get so old?) by Mike Masnik of Techdirt. He was calling back to a 2003 case involving Barbra Streisand’s beachfront property:

How long is it going to take before lawyers realize that the simple act of trying to repress something they don’t like online is likely to make it so that something that most people would never, ever see (like a photo of a urinal in some random beach resort) is now seen by many more people? Let’s call it the Streisand Effect.

And that goes back to 2003 when he wrote:

One thing seems clear these days. If you want to hide something from the internet – you’re only likely to make it more widely available, so you’re often better off not stirring the hornet’s nest. Barbara [sic] Streisand is apparently finding that out the hard way.

It’s slightly ironic that a government whose many assumed were masters of the dark art of social media influence, thanks to the rumours around the Brexit campaign, seems so deeply unaware of how the internet can actually work. By reaching out and persuading The Times to drop the story, they turned a story that was buried a few pages back into the talk of social media for the first few days of the week. Without that additional attention, it would have flown under most people’s radar.

”Yes, Prime Minster”

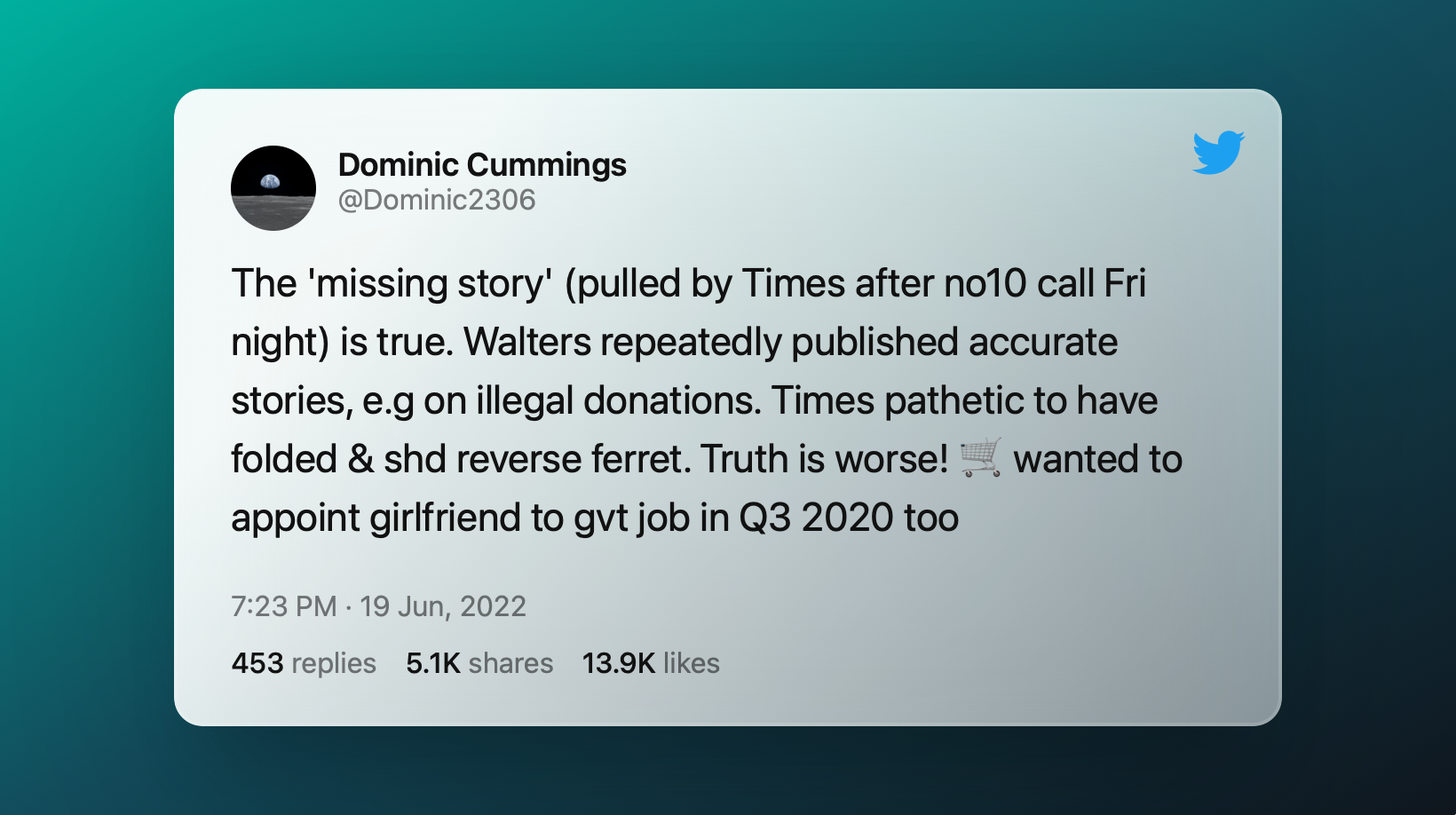

There seems to be little convincing suggestion that the story was untrue — the most straightforward reason for pulling a story. For what it’s worth, one of the people whom many assumed was behind the more manipulative aspects of the government’s social media work has confirmed the story:

What’s baffling to me, though, is why The Times acquiesced to a request to pull it. It’s been dependent on a membership model for years now, and once you make that leap, you have to treat your paying subscribers as member, not just customers. And in this case, they haven’t been doing so.

Even The Spectator, whose generally positive view of Johnson has been in rapid decline, had noted it was… odd. And even followed it up for a while.

It’s bizarre, simply because, by continuing in silence, the senior editorial team of The Times have made it clear that the wishes of an unpopular prime minister are more important to them than those of their paying readers.

The subscribers are revolting

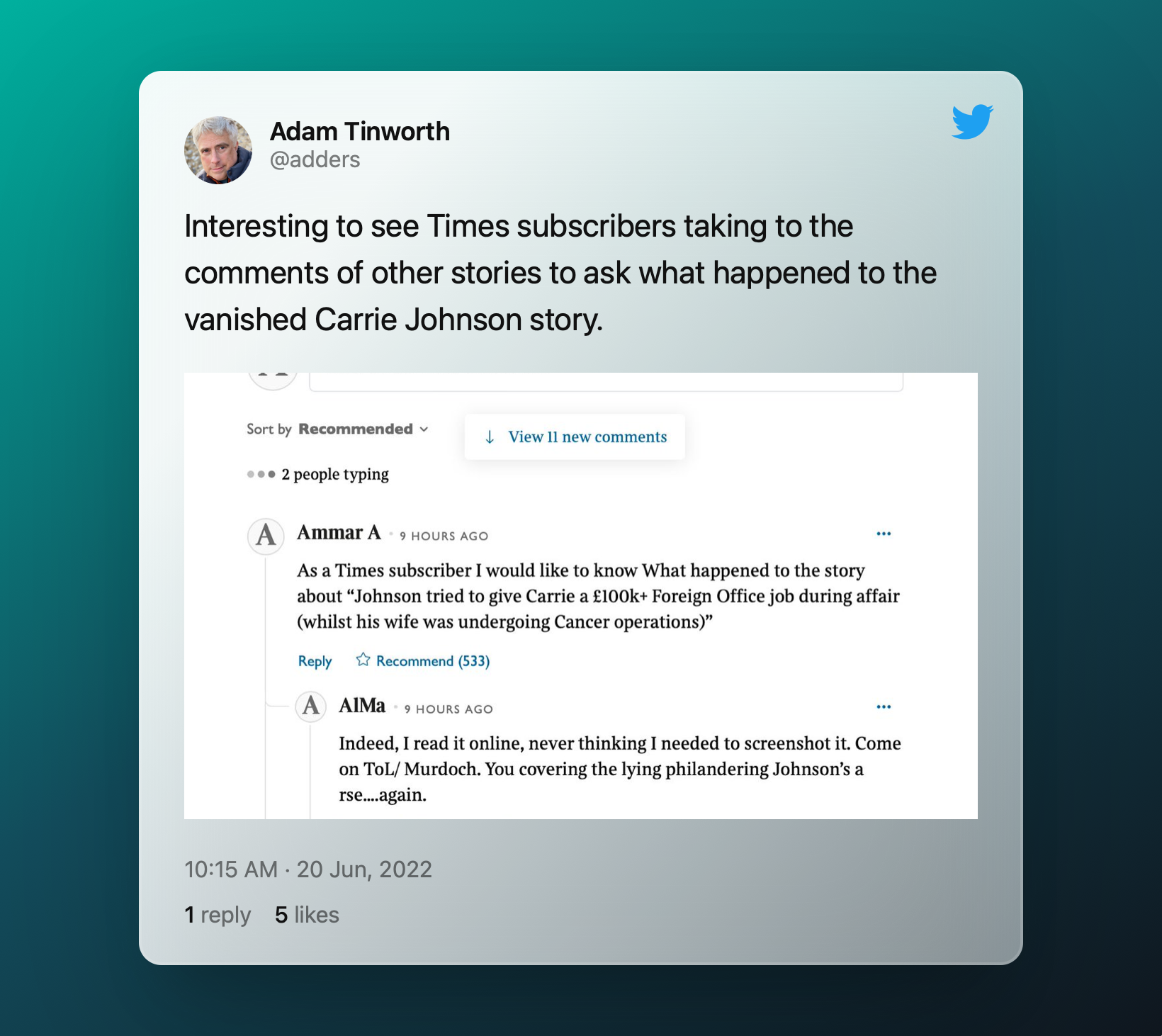

I first noted growing problems among the Times subscriber base on Monday:

Press Gazette’s Born Maher dug more deeply into the story the following day:

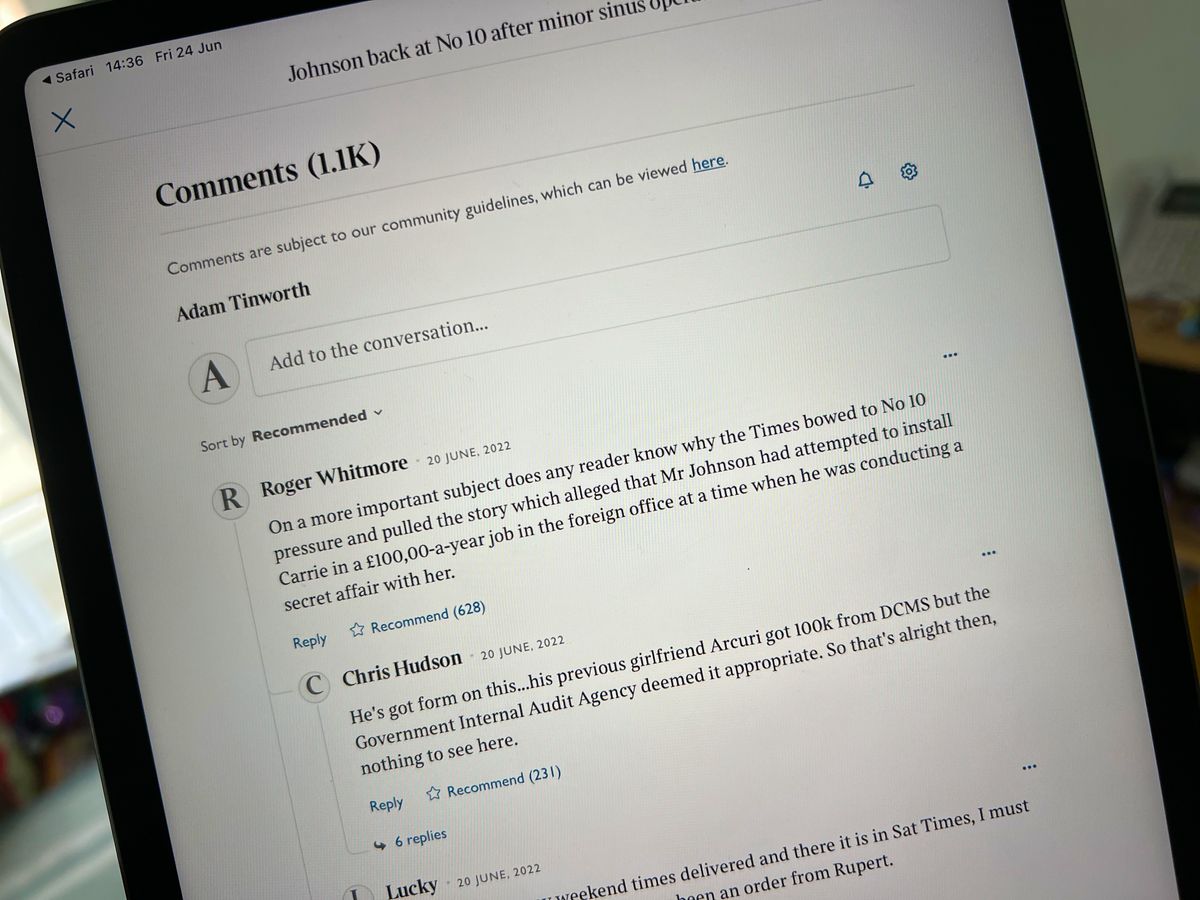

Readers are complaining en masse in The Times’ subscribers-only comment section after revelations the paper spiked an unflattering story about Boris and Carrie Johnson after its initial publication. Comments criticising The Times on its own articles have received hundreds of up votes from other subscribers.

The critical point is in the first sentence: only paying subscribers can participate in the comments on the site. By pulling something like this without comment, The Times is playing a risky game. And it’s a game that might have financial implications for it. If it’s seen as a willing accomplice to a prime minister whose popularity is in steep decline among its core market, it loses the trust that binds people to the brand emotionally.

That might easily translate into cancelled subscriptions — especially with people looking to cut costs as the price of living rises.

Don’t just pay lip service to “members”

A timely reminder that a membership model is not just a fancy way of describing a paywall: it’s a commitment to member-centric publishing. And that carries with it an implicit sense of relationship that the paper has violated with this move.

In reality, the Streisand effect is kicking in on two levels here:

- It’s drawn greater attention to Johnson’s tendency to gift financially lucrative employment to his inamoratas.

- It has drawn attention to the often uncomfortably cozy relationship between the higher levels of journalism and the higher levels of politics.

And the people paying the bills are less than happy. It's to the credit of the audience team at The Times that they've let the comments stand, and let the member vent. But the lack of a clear explanation will lurk in the minds of many for the foreseeable future.