Engaged journalism, membership models and communities under attack: important new research from the Reuters Institute

By deeply researching the audience engagement of three news outlets under sustained assault by hostile organisations, Dr Julie Posetti and team have come up with some vital work

Sometimes, you need to look outside of your own bubble to understand the need for deeper audience enagagement, and the risks of getting it wrong. I’ve spent much of the last 24 hours buried in the new report from the Reuters Institute: What if Scale Breaks Community? Rebooting Audience Engagement When Journalism is Under Fire. And it’s really compelling reading. The team, led by Dr Julie Posetti, with co-authors Felix Simon and Nabeelah Shabbir, have chosen to look at the audience engagement strategies of three emerging digital sites in the Global South.

The report features:

- Daily Maverick in South Africa,

- The Quint in India

- Rappler in the Philippines.

And through those three illustrative examples, they’ve managed to shine a powerful spotlight onto the key issues around community and journalism today.

This is really good stuff.

The key quote, towards the end of the report, that really grabbed me was this:

Open and ‘social journalism’ at-scale, it turns out, was not a final destination (nor necessarily a ‘safe’ one) but a transformative moment on the continuum of audience engagement innovations, and scale has risked breaking community.

That’s a really important idea, and it sums up where we are as an industry right now around audience engagement.

That central headline — that scale breaks community — actually betrays the report’s roots in journalism academia rather than community management. Because the one things we’ve know for a very long time in community management is that scale does break community. It always breaks community. It’s how the community breaks - what the triggering factors are - that’s actually interesting. And, happily, the report digs deep on that.

There are a group of standard ways communities break. For example, Dunbar’s Number is a problem. For something to be a genuine community, you can’t scale too large. You almost always get fragmentation issues if you don’t handle that growth intelligently. More seriously, the larger the audience, the greater the rewards for bad actors. For the simple troll, the attention seeker, the bigger community delivers a bigger reward for their antics. For the misinformation or propaganda purveyor, it offers a bigger surface for dissemination of their politicised content.

Community collapse in news organisations

It’s how scale breaks the communities that the studies publications created that makes this report so interesting, rather than the fact than the simple fact that it does. One interesting thing about the three sites they’ve analysed is that they’re all, to varying degrees, politically activist in nature: the were founded to achieve something, not just report news.

They have purpose, in other words. And that purpose invites opposition - and that can be pretty horrific:

A key feature of these attacks is prolific, brutal, and frequently sexualised online harassment targeting their journalists, in particular the women among them, which has in turn chilled the interaction of their audiences within online communities.

Let’s be clear: this is not trolling. Trolling is largely about getting attention through disruptive behaviour. This is more serious.

This is systemic and organised abuse.

The authors very effectively draw the connections between these actions and the political motivations that underlie them: the attempt to silence the media indirectly, by harnessing the client communities of the site’s enemies to unleash the attack. This, in effect, disguises the true hand of the attacker, making it appear like a more community-driven reaction.

I’m sure I don’t have to draw the parallels for you with events happening in Europe and the US, do I? This, incidentally, is why the decision to study the kinds of outlets they did is so inspired. It provides a microcosm of issues experience elsewhere to be studies, and thus expose patterns that can be seen threaded around bigger news organisations.

The smartest outlets are starting to see themselves as a community of communities - which is the only way to effectively scale a community. And yes, sometimes that involves erecting barriers. But let’s come back to that in a moment.

Platform Capture

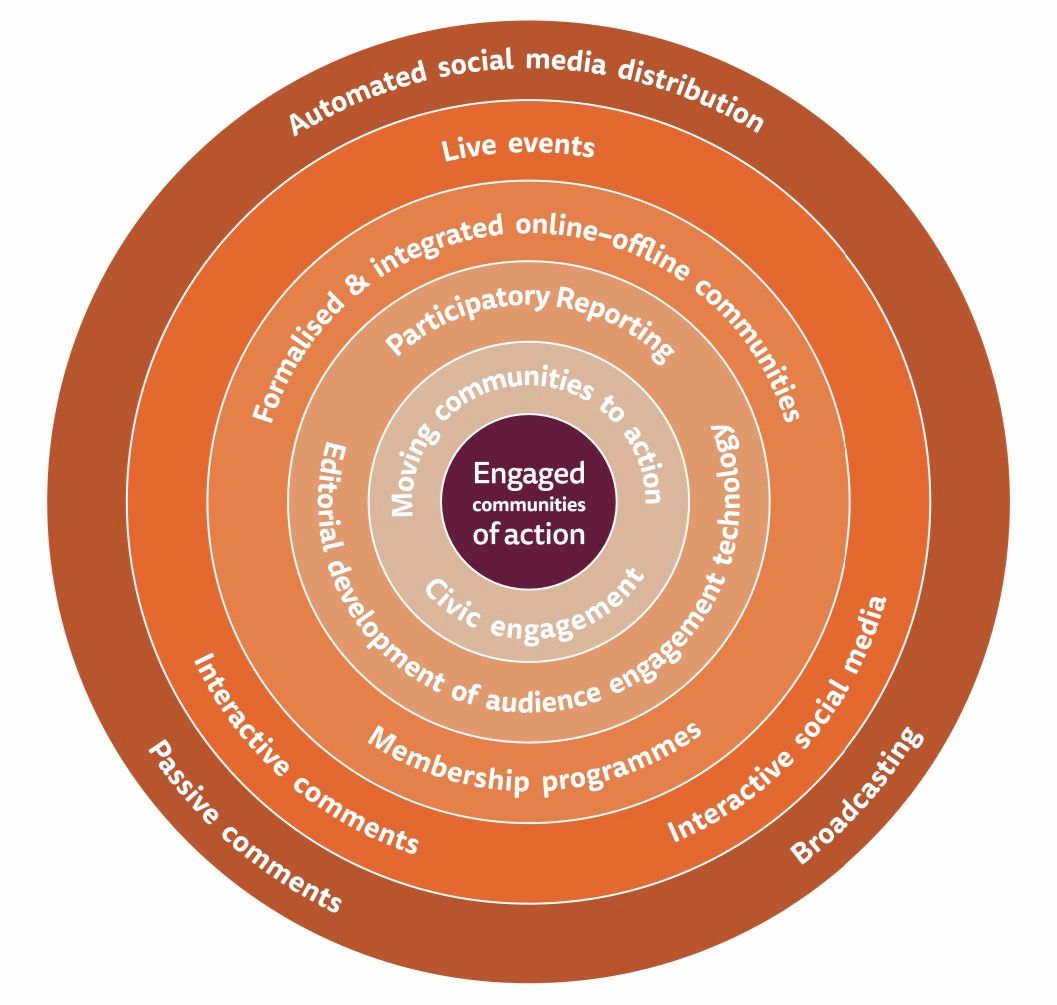

One of the key ideas they introduce is platform capture, as shown here:

Scale can break communities, especially when combined with various forms of ‘platform capture’, including the ‘weaponisation’ of online communities, and frequent changes to platforms’ products and policies.

How does it manifest? Well there are two particular manifestations that it’s worth paying attention to. The first is when you build businesses on platforms your don’t own; and then they change the rules on you. Here’s an example from the report:

WhatsApp users who interact with The Quint are currently being asked to move to Telegram if they want to continue engaging with the news organisation after 7 December 2019. As Head of Audience Growth and Social Media Medha Chakrabartty explains, a referral programme has been rolled out to incentivise existing subscribers:

”We have 26,000 people on Telegram right now, and on WhatsApp we have 100,000–140,000. The challenge is to move them all while keeping in mind they might not be responsive or might have their misgivings.”

The other is when a hostile force essentially captures the platform and community you’ve created. Two of the sites in the report had followed a very mid-2000s model of creating what are essentially community blogging platforms within their site:

Rappler started citizen blogging website X.Rappler in 2015 in response to the demand from Move.PH communities, and from their broader audiences, to be published as Rappler contributors. The platform enabled self-publishing by the blogging community and it was designed in part to manage the workload created by highly successful audience engagement efforts. Daily Maverick began with a heavy emphasis on publishing commentary from informed citizen ‘opinionistas’ (academics, social commentators, etc.), and its investigative reporting repertoire grew from there.

While this worked well in building audiences and engagement in the early stages of the sites, they eventually became targets for focused attacks:

Another casualty of audience toxicity was the X.Rappler citizen blogging portal. It closed in mid-2019 after a series of DDOS (Distributed Denial of Service)24 attacks designed to inhibit Rappler’s user experience, and other security breaches. According to Ressa these included misuse of the platform for propaganda posts and attempts to plant malware. In the end, this audience collaboration project became unsustainable because scale, political attacks, and ‘platform capture’ broke community – in the sense that the community became polluted and ‘weaponised’, and also in the sense that the convergent threats made the collaborative platform unmanageable for Rappler.

Contained Communities

One of the responses to both forms of platform capture is to create and police your own spaces. And guess what an effective barrier to infiltration — or wholesale infiltration, at least — can be? Money. Yes, membership models are about more than just revenue:

None of the news organisations studied here began with a membership programme, but in the past year each of them has turned to membership as a way of deepening audience engagement in a ‘safer’ space and monetising the loyalty generated by their independent journalism and their civic activism in reference to attacks on democracy and media freedom.

Too often “membership” is a code for “paywall”, with outlets paying lip service to genuine engagement with their paying subscribers. This is not at all the case in the outlets covered in the report. The memberships both help sustain the sites financially, but also bring community benefits to both the editorial staff and the members.

As an aside, one of the things I talked with John O’Nolan about for the Ghost 3.0 post earlier in the week, is the value that closed spaces sometimes bring to communities. It’s certainly one of the things he sees as valuable in the new functionality they’ve added, granting publishers the ability to create conversational community spaces that are hidden from general view.

In short: sometimes the walls allow the community to exist, if that community is under siege. And that’s the key lesson that most of these publications have learned. The free, open web is fine for many uses. Sometimes the big closed platforms are, too.

But if you’re serious about relationships with your members, you have to engage with them online and offline, in ways you both can control and which you are able to police.

Don’t just pay lip service to membership

It’s worth letting one of the key interviewees for the report have the final word on this:

If the premise of the whole social news network company is to really be social and build a community around it, and if you really want to hear what people have to say, then you have to also meet them on the ground,’ Rappler’s former Head of Digital Communications and Move.PH Stacy de Jesus says. ‘Plus, if it’s community-building, it’s relationship-building. So, it’s very important for us to really see people.’

Amen.

- You can download Scale Breaks Community? Rebooting Audience Engagement When Journalism is Under Fire from the Reuters Institute site.

- The authors have summarised their findings for Nieman Lab.

Sign up for e-mail updates

Join the newsletter to receive the latest posts in your inbox.