As social platforms decline, publishers have an opportunity

As the dominant social platforms change, and pivot away from being networks to media destinations, publishers could step into the gap they leave.

Why start talking about community again now? Surely, that’s done? Publishers are focusing less on Twitter and Facebook, and the existing social platforms are moving towards a creator-centric model. The social networks are becoming yet another arm of the broadcast media. Social media is dead, right?

Well, no.

One era of online community is drawing to a close, for sure. Over the last 15 years, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram et al have been slowly gathering up all the distributed online communities found on forums, and blogs, and on Usenet, and on mailing lists — the relics of the previous age of online community. And then they stuffed them down their massive corporate maw.

What they offered — a seductive blend of silky smooth ease of use, and steamy hot numbers of people making finding your tribe ever easier — was compelling. But that offer also had a toxic downside: a lack of consequence for bad behaviour, and ever-increasing incentives for behaving badly to garner attention. That age is ending because the financial balance no longer makes sense — Meta is cutting another 10,000 staff, for example — and people are scurrying away from the toxicity. As Kevin put it in response to yesterday’s piece:

I was thinking about this on my morning run. I've been much quieter online for much of the past decade. Some of it is down to time. Some of it is due to disruption in the industry and my career. A lot of it is conflict avoidance.

— Mr Anderson (@kevglobal) March 15, 2023

Swapping “network” for “media”

The focus is swinging towards TikTok and its clones — and that’s interesting because almost nobody heads to that platform to see what their friends are up to. TikTok is social media in the same way that YouTube is social media: a publishing platform anyone can access. It is not, in any meaningful sense, a social network. And that means that there’s a space opening up that TikTok can’t fill.

As I’ve noted before, humans are inherently social creatures. Hybrid work is always more likely to succeed than complete remote work because humans like being around each other. We like to form groups and networks, to keep in contact with each other. And, for the moment, that activity is largely becoming self-contained, and self-managed, as people make WhatsApp groups to chat, or start their own Discord communities. And that largely covers the need for small communities, those lurking under Dunbar’s number.

The human scale social network

But what of communities in the middle? Those that sit between the “everyone” of the big social networks, and the “just us” of the WhatsApp groups? The niches that professions, and hobby groups, and sports fans and so many other identity groups live in? These are generally just a little too large to be managed in an ad hoc way by community volunteers. They cost money to host and moderate. But they provide a vital way of allowing people to gather around a subject.

I’ve encountered many examples of the critical role they’ve played in people’s lives. There was the impact of farming forums on the agricultural community back in my RBI days. More recently, I’ve encountered Sidetracked editor Alex Roddie talking about the impact of the UK Climbing Forums on his working and personal lives, both in his book and on his blog. I’ve even seen friendships forged in (whisper it) comments sections.

Where people need a place to gather, and information to feed their discussions, there’s an opportunity for publishers. And, as we’ll see, there’s a commercial incentive for them to do so.

Online Communities in the 2020s

- Folks, we need to talk

- Social Media will never die

- To come

- To come

The Anti-Social Artifact

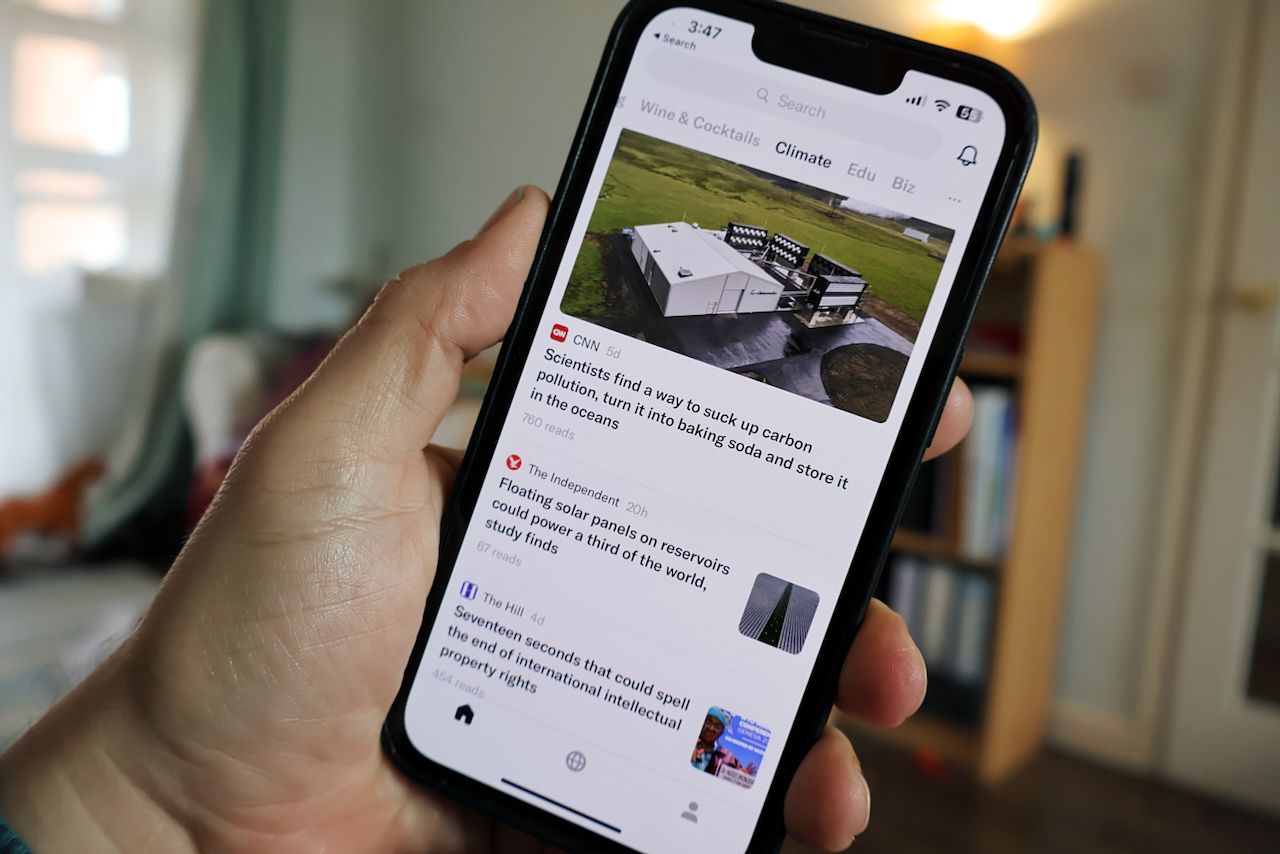

As I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, the founders of Instagram have started a new app — for news reading. I’ve not had much more than a cursory play with it, but a Techcrunch piece delves deep into their thinking:

“It might be cheesy to say, because I’ve now said it a bunch of times, but I feel like the worst part about social media is that it’s social,” Systrom says. “I think the ‘social’ part of social media — for a long time, in terms of information consumption — has been a hack to filter for information that would be interesting to you. But we now don’t need that hack, because we can learn what’s interesting to you,” he continues. “We can quantify it. We can build profiles. And then we can serve you content that is both high-quality, balanced and interesting to you.”

What’s also interesting is that they see the app as a very selective place for news. You’re not going to find news from every site on the web in there, but a tight selection curated by the team:

“When I say taste, I mean the top of the funnel in our system — the publishers we choose to distribute,” notes Systrom. “It’s not a free-for-all. We don’t crawl the entire web and just let everything go in.”

This isn’t really a surprising from Systrom, who has always prided himself on his taste. But it will become an issue, should Artifact every become a major player in the news-reading space.

Quickies

- 👮🏻♂️ An increasing number of EU countries are ruling that Google Analytics violates GDPR.

- 🔎 Bing is growing, thanks to the ChatGPT integration. We might start having to pay attention to it soon.

- 💰 Amazon’s advertising business is now bigger than that of what’s left of the newspaper business.

- 🐘 Automattic (the people behind WordPress) have acquired a plugin and its developer, to integrate WordPress more deeply with the Fediverse, of which Mastodon is part. Worth watching.

- 🎂 I thought my 20 years was impressive — but OG blogger Jason Kottke has just reached 25 years.

Reader Recommendation

Peter Torres Fremlin recommends:

It’s a lovely response to Musk's appalling behaviour from the very community he was mocking…

Sign up for e-mail updates

Join the newsletter to receive the latest posts in your inbox.