Social Media, chat apps and journalism: people's news discussions are becoming private, not public

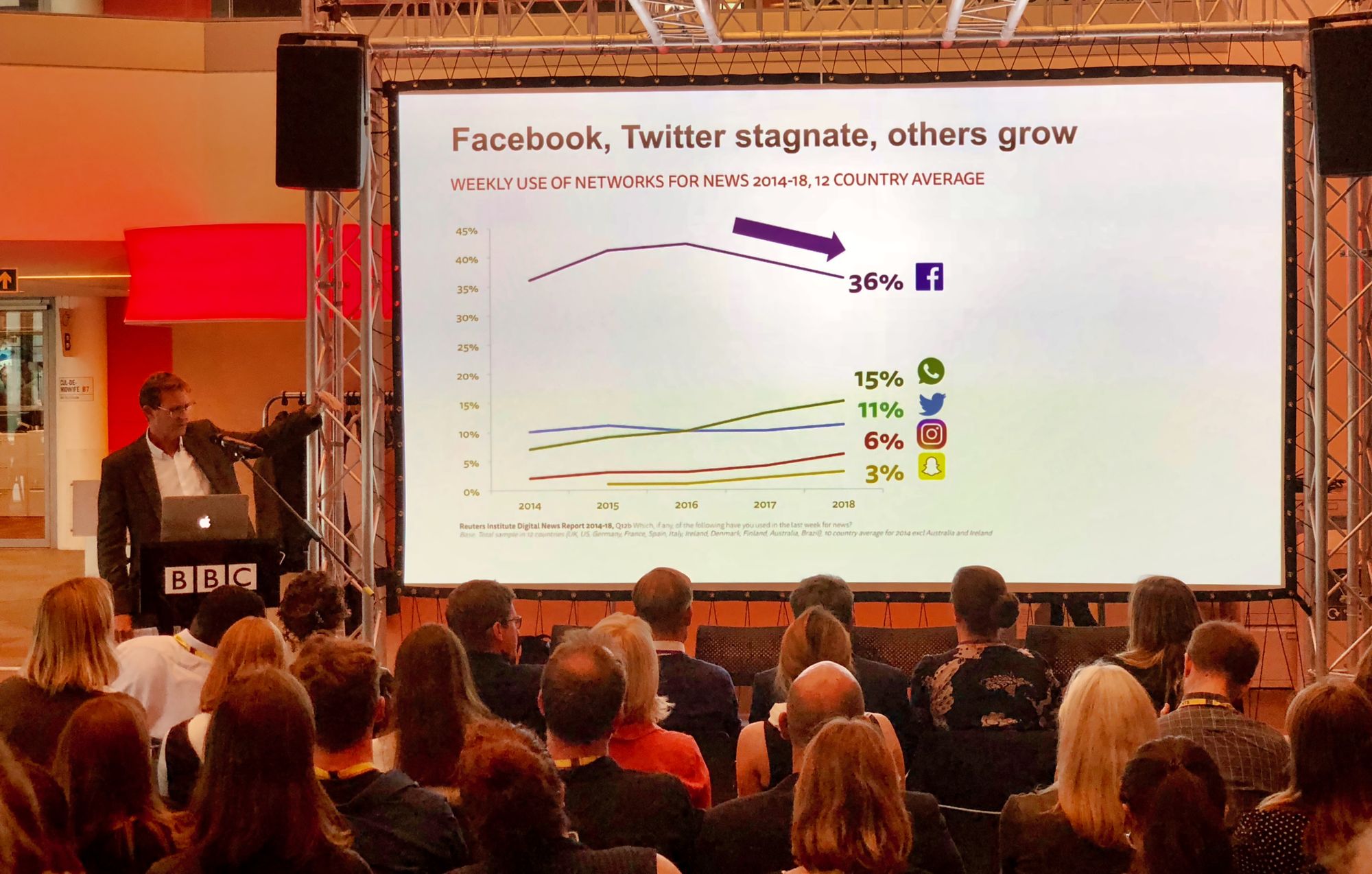

Facebook is in decline and the chat apps are rising. But it's more than algorithm changes, but a shift in people's behavior - how do we adapt?

If there's one thing we need to know more about in journalism, it's how people get their news, why they get it that way, and how they feel about it. The news that the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism had commissioned a report entitled News in social media and messaging apps was heartening, and when offered a chance to attend the launch, I couldn't resist.

After a welcome from Mark Frankel, the social media editor at our host for the evening, the BBC, Nic Newman from the kicked off the main part of the session by setting some context - most notably the decline in Facebook as a source of news for many people — even if it still remains the biggest single source for many publications — with chat apps rising to replace some of what had been lost. What is driving this change? That's what Jason Vir's research set out to answer.

Here are my quasi-liveblogged notes from the session:

Jason Vir

For many people, Facebook is very much part of their daily routine. Some of it is purposeful, and some of it is filling idle moments - or even just habit. There’s also a distinct movement of people trying to restrain their use of the social network.

Facebook has moved from being a network for your friends to being a central hub for relationship management, people felt. That has led to some reduction in personal sharing, as people become aware of the wider group seeing what they're sharing - the consequences seem higher. It can also be overwhelming - there’s too much information for some people to take in. People are more hesitant before posting, and are starting to avoid some topics. (Bloggers note: This is the context collapse I’ve written about before). The overly-aggressive politicial tone has been one reason people withdraw from discussions on Facebook.

How about Fake News? People struggle to think of examples of when they’ve seen it. The shift in the algorithm away from news got a mixed reaction - some people felt it was good, some felt that news was a core part of the experience.

Removing the mask

On messaging apps, news fuels some of the conversations they’re having in persistent group chats - with friends, families or work colleagues. These closed platforms allow people to feel that they can take their masks off, rather than using a constructed identity on more public social media. It seems to allow easier disagreement without conflict.

In Brazil audio was heavily used to share news or information.

Facebook is largely perceived as a "public" space, and WhatsApp as a "private" one. You interact with smaller groups - and often more trusted ones - in the chat apps. People are wary of large group chats - so news brands are unlikely to be able to get their own large scale group chats going.

People pay attention to the news story, and the headline in particualr, and then the source as a secondary piece of information. The friend sharing it also makes a difference.

People do check URLs in chat, but are attracted strongly by images.

Panel:

- Jason Vir, Kantar Media

- Mark Frankel, social media editor, BBC

- Beth Ashton, head of social, Telegraph Media Group

- Karyn Fleeting, head of engagement, Reach

Mark Frankel (MF): One of the interviewees talked about judgement and being judged. There is a perceptible shift around misinformation - and people’s willingness to join in conversations about things that might affect their lives. How do we reach people in private spaces? Social media is becoming more relevant, not less - but to people who want to share privately.

Karyn Fleeting: I was interested to see WhatsApp described as a trusted friend. That would explain why we see such high clickthrough rates from WhatsApp. The groups we’re running are broadcast lists, rather than discussion groups - a few headlines once or twice a day. In some cases WhatsApp lists were set up as stopgaps, while apps were built - but they’ve been very successful.

We have over 100 Facebook groups, some open, some closed. Closed groups promote a sense of exclusivity.

Beth Ashton: People trying to quit Facebook is a lot like people trying to quit smoking. They try but often they fail and come back.

We’ve been thinking about the people who would seek you out if they weren’t getting you in the feed. You don’t create groups for people who won’t seek you out. Instagram - the show off environment - it’s a bit like Facebook but kinder. The journalists are more willing to put things up there, more personal things, that they wouldn’t on Twitter or Facebook.

MF: There’s a declining interest in the Facebook feed, and growing interest in groups. Should we go to a group with a story idea, test it and then go to the feed?

KF: It has transformed our Facebook strategy - we’ve moved towards optimising our Facebook posts for conversation - meaningful engagement is really just chatting. We have about 300 facebook pages, some have 100 Likes, others have millions. But we have had to transform how we approach it. We are doing lots, lots more with groups. We have to pivot and change tactics regularly.

BA: There’s no scope for discovering the things you didn’t know you wanted to know any more on social media. Should all of news be punished for Fake News? I don’t think so. We’re all being tarred with the same network brush.

MF: We all used to applaud the fact that several thousand people who saw your story in Facebook would come to the site - but they only read the first paragraph. the bounce rates were terrible. There’s an opportunity here to create more popular, long lasting content based on the conversation in the group. It’s worked for us. Yes, you’re playing Facebook’s game - but you are looking at it in a different way to you were 12, 18 months ago.

KF: We’ve been doing more with live events and podcasts recently. We have limited resources, and so you have to decide which ones you invest in.

MF: Fake News using our brand in WhatsApp is a problem. You can’t control the information flow - and that’s a platform issue. There’s an opportunity here. i talked to an Indian journalist who specialised in getting in WhatsApp groups - and he was able to piece together how the conversations were developing - and that they were being controlled by one organisation. You can find WhatsApp groups to join by being on Facebook - or Reddit. Become part of that ecosystem - but it's a fishing expedition.

KF: It’s been wonderful finding stories in facebook groups. They’ve opened up a closer relationship with our readers. We get story ideas much more easily and frequently.

BA: A lot of our reporters use social to find stories. We’re getting pretty good at verification now. But it's important to work out how to tell stories on the platforms, rather than just pushing links to them.

Facebook Messenger? Everything about it feels so robotic.

Ashton cites the example of Victoria Beckham chat bot. It’s hard to use.

Nic Newman: People only use Messenger when they don’t know someone’s phone number, at least taht's what the focus groups suggested.

BA: We built our politics and policy Facebook group by the journalists putting a lot of work into it beforehand.

MF: Admins can heavily restrict which members can join a Facebook group. The creation and participation in groups presents a challenge around the diversity of newsroom, though. Do we have people who understand the issues and the dynamics?

4chan and Gab are absolutely horrible in many ways. I had to take screen breaks and walk away after some of the things I saw - but it brought me to other spaces online, like gaming communities, and LGBT rights forums and so on. These are communities we don’t spend enough time thinking about. There are Discord servers where people play games and talk about Trump and guns. We don't think about these other communities.

BA: The same place you can hide you identity can be the place where you feel safe.

Some thoughts from me

It's clear, around nine months after Facebook pulled the rug from under us, that we're still dancing to Facebook's tune, either by jumping into groups, as they told us to, or by going to alternative platforms like WhatsApp or Instagram, both owned by Facebook.

Also almost exclusively Facebook owned products

— Sue Llewellyn (@suellewellyn) September 12, 2018

That said, there were some very encouraging signs. The social teams represented are genuinely swinging back towards conversation — "chatting" as Fleeting put it — over pure promotional broadcast on social media. And there's an acceptance that WhatsApp and other chat apps might be more about engagement and research than directly attracting traffic.

However, I'd like to see more people actively planning for the possibility of Facebook pivoting again — away from groups, for example — by starting to explore ways of turning platform-mediated engagement into a direct relationship, via a newsletter or maybe even some on-site community features.

Indeed, Frankel's comments about exploring those communities that exist outside the main platforms gave me a real sense of deja vu as that's exactly the sort of initiatives many publishing organizations were doing 12 years ago, before the platforms sucked up all the attention and resources. I suspect we should be revisiting that sort of work — but how much institutional knowledge have we squandered in the meantime? I can think of precious few of the mid-2000s cohort of engagement experts who are still working in newsrooms.

That's a big loss of expertise that we could probably be using right now.

- The full report is available for download.

- Nieman Lab have published an excellent summary of its findings.

Sign up for e-mail updates

Join the newsletter to receive the latest posts in your inbox.