Four things publishers should give up in 2023

Digital publishing moves so fast it can be hard to keep track of what works, and what doesn’t. Here are the things you need to be letting go of right now.

Giving things up is never easy, but it's deeply beneficial to us. Whether it's letting go of past slights, decluttering our homes — or finally abandoning publishing recieved wisdom that is dragging you backwards in 2023.

So, here's either a late set of New Year's Resolutions or an early list of things publishers should give up for Lent — and for the foreseeable future, too. And they're all based on mistakes I've seen publishers making over the last year or so.

Open Rates

The newsletter open rate is dead, killed by Apple in 2021. And yet, it lives on, zombie-like, as people keep obsessing over it. Now, I’m as guilty of this as anyone. I can tell you exactly the open rate of my last couple of newsletters. But the core thing to me is trends, not the absolute number. I can see that those numbers are going up, not down, and that's more important than the absolute number. Why? Because the open rate itself is a lie.

It’s a lie because people on Apple devices, using Apple’s mail apps, and who have turned on email privacy (which they’re prompted to do) show up as opens whether or not they actually ever open the email. Apple email privacy protection inflates your open rates.

The greater the percentage of people on Apple devices, the more your open rates are lies. On the other end of the scale, I have some subscribers using hey.com email addresses — they look as if they never open the emails, even though I know at least some of them do. That email service handles privacy differently, by blocking tracking pixels completely.

You need to be looking at variance in open rates, not the absolute figure. You need to be monitoring subscriber churn, and conversion rates. Likewise, you should look at click-through rates and even more general engagement metrics, like the ones that are handily shown on my Ghost dashboard that incorporate signed in site visits, as well:

If you’re just using open rates, you’re lying to yourself, and you’re lying to your journalists, too.

Keywords

Are you still working off a spreadsheet of targeted keywords? Oh, dear. I have sobering news for you: you’ve become the 2020s equivalent of a 2010s publisher who was still hiding keywords on the page, or relying on the meta keywords field to get SEO traction.

The age of the keyword is all but done, and we can thank our friend AI (or, more properly, machine learning) for that. Google search result are now largely determined by an ever-growing range of ML algorithms that rejoice in names like MUM, BERT and RankBrain. They all seek to determine searcher intent — and deliver results based on that.

For years now, you could have two people sat next to each other putting the same keywords into Google and each would get different results. That’s personalisation at work. Now, though, it’s even more likely, as the algorithms could decide that the two searchers had entirely different intents, and show them results based on those different information needs.

Forget planning content for keywords, start planning content for the questions people have and the problems they need to solve. That’s intent.

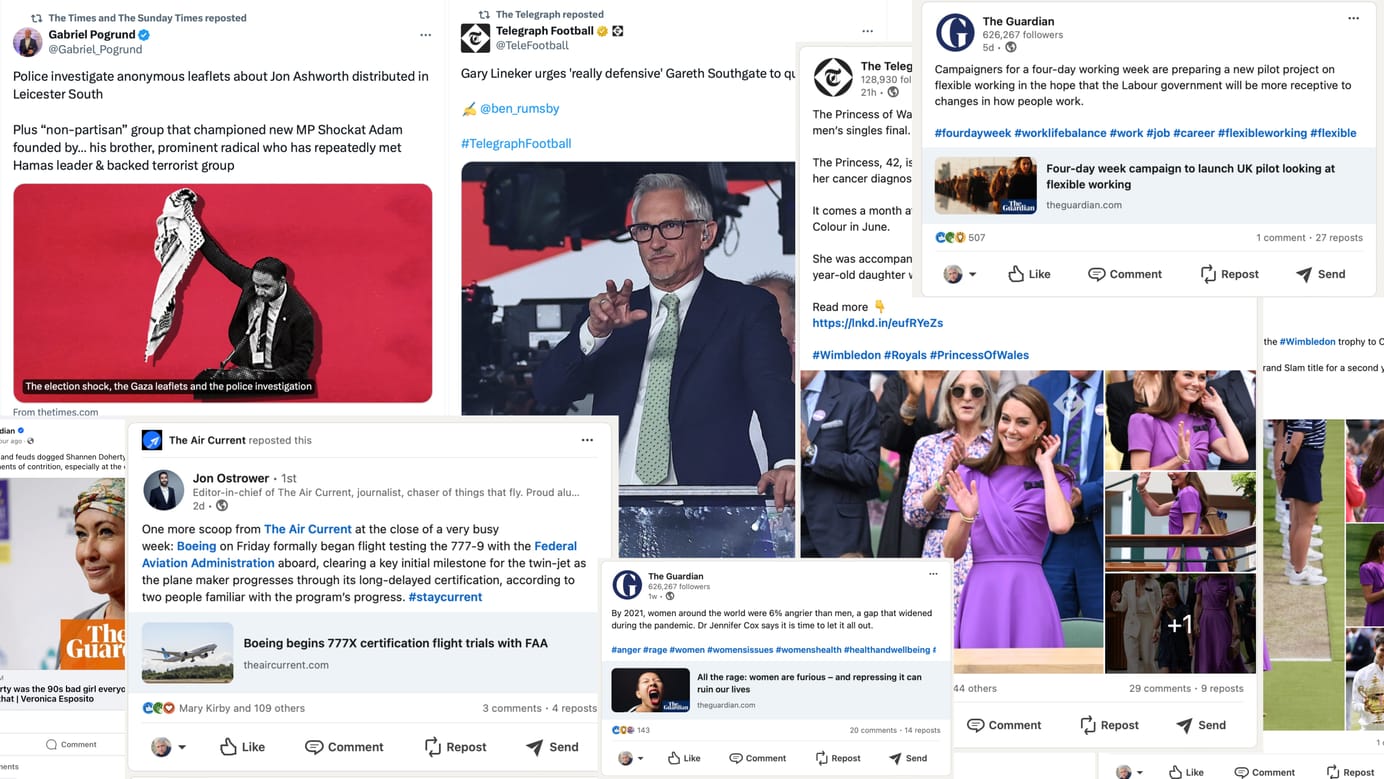

One of my great, unwritten pieces for this site is “Why Twitter is a trap for journalists”. And it is. Journalists have been lured into spending just too much damn time on Twitter, and acting in ways that are genuinely harmful to the reputation of the press as a whole.

We’ve known for a long time that Twitter is not a great source of traffic for most sites. A former student who was working in audience at one of the major UK tabloids told me once that Twitter almost never figured into their traffic planning, despite the amopunt of time their journalists spent on there. This has only got worse since the Musk takeover.

So, wind down your exposure to the platform. It’s time to ignore doom-mongers about Mastodon, who don’t remember what Twitter was like in 2007 (when you either used it on the web on your PC, or had it delivered via SMS to your phone). Listen to those who were around for the early days of today’s networks, and know how their use takes time to grow. Invest a fraction of the time you’re putting into the existing platform into the emerging one — and reap the benefits.

TikTok

Oh, controversial one here. I have spent nearly 18 years of my life evangelising the role of emerging social networks in journalism. I was hyping Twitter back when people thought it was a waste of time, a place where people talked about what they had for lunch. (I passed my 16 years on Twitter in December 2022. When I told Charlotte Henry this recently, she immediately looked concerned and asked if I was OK…)

So, then. Why am I saying that publishers should be wary of TikTok, the new hotness in social? Well, there are two reasons. The first is that TikTok, in common with Instagram, and unlike earlier social platforms, is a roach motel: attention goes in, but it never comes out. It’s very, very hard to drive traffic from the platform to anywhere else. And so, it’s very hard to turn the audience that accidentally sees you on TikTok into an audience you actually have a relationship with.

Sure, if you’re a big publisher who can afford to wait for the long-term conversion, for the 20-something who sees you on TikTok now, and who will eventually become a reader in five years, go for it. More power to you. But for smaller publishers with more limited audience and social resources? Think carefully.

The China Factor

And yes, it’s worth remembering that TikTok is, essentially, owned by China. At the very least, they’ve proved themselves more than happy to use the data TikTok collects in ways we would consider unethical, like tracking journalists.

Do we really want to be helping build the presence of a platform controlled by an antagonistic foreign power? China has no scruples about using this sort of soft power to further its geopolitical ambitions.

And, hovering on the horizon is the threat of China invading Taiwan. If that happens, not only will a deep tech winter hit, but you can also say goodbye to any audience you’ve built on the platform. And that might happen anyway — the US, at least, is giving serious thought to banning it.

One you have to give up: Google Analytics

So, you use Google Analytics? Well, it’s going away. The version you’re familiar with, often called universal analytics, is being “sunsetted”, to use that horrible Silicon Valley euphemism. It will stop collecting data from July, and from then on, you’ll have to use GA4 — Google Analytics 4 — the new version.

It’s very different.

If you’re not already, you need to have the two running side-by-side as soon as you possibly can. You need to start training your staff, or yourself, to use the new version as soon as you can. The clock is ticking, and given how useful historical data is in forwards content planning, the sooner you start capturing data into GA4, the better.

Worse than that, Google is only committing to keeping Universal Analytics data around for six months, so you have to consider a way of exporting and capturing those historical traffic figures in a way that’s usable into the future.

Just over five months to do it, friends. Tick-tock tick-tock…

Sign up for e-mail updates

Join the newsletter to receive the latest posts in your inbox.